Case Study - 'upgrade-stripe' Agent Skill

In which I deep dive on a Stripe Skill, and what it means for the industry.

In my last article, I wrote about why we designed a simplified testing framework approach to help technical writers test the code examples in our documentation. A major component of this is the unified Expect.that() comparison API we created to give writers a single entrypoint to validate our code examples. This API abstracts all of the field/value comparisons that validate that when we execute the code example we show in the documentation, it actually produces the output we show in the docs. We designed this system as a shortcut so writers wouldn’t have to learn individual assert syntax and do comprehensive testing for every code example they add to the docs.

The early proof-of-concept of this comparison tool was a simple script I wrote in JavaScript. Usage looked like this:

it('Should return filtered output that includes the three specified person records', async () => {

// Set up the database and run the code example

await loadFilterSampleData();

const result = await runFilterTutorial();

// Create a file that contains the output we show on the page.

// This is a change from hard-coding it in the page text

const outputFilepath = 'aggregation/pipelines/filter/tutorial-output.sh';

// Call the comparison script and expect the results to match

const arraysMatch = outputMatchesExampleOutput(outputFilepath, result);

expect(arraysMatch).toBe(true);

});

This was - ok - but we discovered pretty quickly that we needed to handle a lot of complexity in this script. We needed to expose configuration options so writers could specify aspects of the desired behaviors. And this started to get very wonky with a lot of differences when we wrote versions of this across the different languages we support.

Once it became apparent that the surface area was a lot deeper than I thought, I sat down and had AI help me write a spec for what we’d need to handle. I drafted the initial spec for C#, and then pointed AI at our actual documentation to examine the examples we show and find things that we didn’t handle yet in the spec. After many rounds of this, and across the different languages, I came up with a somewhat complete list of things we needed to handle, and this became our first spec.

If you care for a deep dive, that spec is still in our repo at Comparison Functionality Spec for Example Output, although we’ve outgrown it a bit since then. I’ll be making a new version of this in the future to reflect updates, and will use that as a basis for the unified core utility we’d like to build. At the moment, we are maintaining six versions of this comparison utility across the different languages. We want to consolidate the core comparison functionality into a single lib with language-specific wrappers - i.e. a comparison tool with SDKs - but we’re still in the phase of validating this approach before we invest more engineering time.

The spec outlined the key features I needed to build to enable comparison functionality for our existing corpus of code examples:

After living with the functionality for a bit, I realized we needed to add three more things:

MongoDB documents often contain dynamic fields that vary between executions. The _id field is the most obvious example - MongoDB generates a unique ObjectId for every document unless you explicitly provide one. But there are others: timestamps, UUIDs, session IDs, and any field that contains generated or time-based data.

Consider this expected output we might show in our docs:

{

_id: ObjectId('507f1f77bcf86cd799439011'),

name: 'Alice',

createdAt: 2024-01-15T10:30:00.000Z

}

When a writer runs this code example, they’ll get different values for _id and createdAt every time. The comparison would always fail, making the test useless.

Our solution: field-level ignoring. Writers can specify which fields to skip during comparison:

Expect.that(result)

.withIgnoredFields('_id', 'createdAt')

.shouldMatch(outputFilepath);

The implementation is straightforward but applies recursively. Here’s the core logic from our Go implementation:

func shouldIgnoreKey(key string, options *Options) bool {

if options != nil && options.IgnoreFieldValues != nil {

for _, ignoredField := range options.IgnoreFieldValues {

if key == ignoredField {

return true

}

}

}

return false

}

This check happens at every level of nested object comparison. If you have a document with nested objects containing _id fields, they all get ignored. This lets writers focus on the semantically meaningful parts of the output without worrying about generated values.

The design decision here was explicit: we chose to ignore entire fields rather than just their values. An alternative approach might have been to use placeholder patterns like { _id: "<any>" } in the expected output. But that would require writers to include those fields in every expected output file, adding noise. By ignoring at the API level, expected output files stay clean and match exactly what we show in the documentation

This one is my favorite. Technical writers have a long tradition of using ellipses (...) to indicate “there’s more here, but it’s not important for what we’re showing you.” We use this constantly in documentation to focus readers on the relevant parts of output while acknowledging that real output might be more verbose.

Here’s a real example from our aggregation tutorials:

{

person_id: '7363626383',

firstname: 'Carl',

lastname: 'Simmons',

...

}

That ... tells the reader “this document has more fields, but we’re showing you the ones that matter for this example.” The problem: that’s not valid JSON. It’s not valid JavaScript. It’s a documentation convention that has no meaning to a parser.

But I really didn’t want to force writers to choose between documentation clarity and testable output. So we built a three-level ellipsis handling system.

The simplest case: an ellipsis as a field value means “any value is acceptable here.”

{

_id: "...",

name: "Alice"

}

This matches any document with name: "Alice", regardless of what _id contains. The implementation checks for the literal string "..." and short-circuits to return a match:

if expectedStr, ok := expected.(string); ok {

if expectedStr == "..." {

return ellipsisResult{handled: true, matches: true}

}

}

We also support prefix matching with a trailing ellipsis. If the expected value is "Error: connection...", it matches any string starting with "Error: connection". This is useful for error messages that include dynamic details.

For arrays, we support two patterns. An array containing only an ellipsis matches any array:

["..."] // Matches any array, regardless of contents

This is useful when you want to assert that a field contains an array but don’t care about its contents.

We also handle ellipses as array elements to indicate “there may be more elements here”:

[

{ name: "Alice" },

"...",

{ name: "Zoe" }

]

This would match an array that starts with a document containing name: "Alice" and ends with one containing name: "Zoe", with any number of elements in between.

The trickiest case: an ellipsis as a standalone property to indicate omitted fields. When we detect the pattern { "...": "..." } anywhere in an expected document, we switch to “lenient mode” for that comparison. In lenient mode, the actual document can have fields that don’t appear in the expected document without causing a failure.

{

name: "Alice",

"...": "..."

}

This matches any document that has name: "Alice", even if it also has age, email, address, and fifty other fields.

We’ve been condensing this to an even briefer implementation that feels more natural:

{

name: "Alice",

...

}

The hard part wasn’t the matching logic - it was getting these patterns through a JSON parser at all. JSON doesn’t allow unquoted ellipses, trailing commas, or any of the other syntactic shortcuts that writers naturally use.

Our solution: a preprocessing step that transforms MongoDB shell-style output into valid JSON before parsing. Here’s a snippet:

// Quote unquoted ellipsis patterns

input = quoteUnquotedEllipsis(input)

// Convert standalone ellipsis to field notation

input = convertStandaloneEllipsisToField(input)

// Remove trailing commas

input = removeTrailingCommas(input)

The quoteUnquotedEllipsis function is particularly careful - it has to distinguish between an unquoted ellipsis that needs quoting ({ key: ... }) and an ellipsis inside a quoted string that should be preserved ({ plot: "The story continues..." }). This requires maintaining string context while scanning:

for i < len(str) {

char := str[i]

if char == '"' {

// Inside a double-quoted string - copy verbatim until closing quote

// ... (skip over string contents without modification)

} else if char == '.' && i+2 < len(str) && str[i:i+3] == "..." {

// Found potential ellipsis outside a string

// Check if followed by delimiter (space, comma, }, ])

if followedByDelimiter {

result.WriteString(`"..."`) // Quote it

}

}

}

This kind of careful string-aware transformation appears throughout the preprocessing code. It’s not glamorous work, but it’s what lets writers use natural documentation conventions in their expected output files

MongoDB has its own type system that extends JSON with things like ObjectId, Decimal128, and various date representations. These types serialize differently depending on context - the MongoDB Shell shows them one way, Extended JSON shows them another, and each language driver has its own native representation.

Here’s the same ObjectId in different formats:

// MongoDB Shell

ObjectId("507f1f77bcf86cd799439011")

// Extended JSON (canonical)

{ "$oid": "507f1f77bcf86cd799439011" }

// In a Python driver response

ObjectId('507f1f77bcf86cd799439011')

// What we ultimately compare

"507f1f77bcf86cd799439011"

Our comparison utility needs to recognize all these formats and normalize them to a common representation for comparison. We chose the underlying value (the hex string for ObjectIds) as our canonical form.

The normalization happens at two stages. First, when parsing expected output files, we transform MongoDB-specific syntax into parseable JSON:

// Handle ObjectId constructor

objectIdRegex := regexp.MustCompile(`ObjectId\(['"]([^'"]+)['"]\)`)

input = objectIdRegex.ReplaceAllString(input, `"$1"`)

// Handle MongoDB extended JSON date format

mongoDateRegex := regexp.MustCompile(`{\s*"\$date"\s*:\s*"([^"]+)"\s*}`)

input = mongoDateRegex.ReplaceAllString(input, `"$1"`)

Second, when comparing actual results from driver calls, we normalize BSON types to their string equivalents:

func normalizeValue(value interface{}) interface{} {

switch v := value.(type) {

case bson.ObjectID:

return v.Hex()

case bson.Decimal128:

return v.String()

case bson.DateTime:

return time.Unix(int64(v)/1000, ...).UTC().Format(time.RFC3339)

case time.Time:

return v.UTC().Format(time.RFC3339)

// Normalize all numeric types to float64 for consistent comparison

case int, int32, int64, float32:

return float64(v)

}

}

A subtle but important detail: we use class name string checking rather than type assertions where possible. In Python, for instance:

if value.__class__.__name__ == "ObjectId":

return str(value)

This approach is more resilient because the BSON types might not be importable in all environments where the comparison runs. If a test environment doesn’t have pymongo installed, we still want the comparison utility to work with pre-normalized data.

Date handling deserves special mention. Dates can appear in multiple formats - ISO 8601 with varying precision, Unix timestamps, MongoDB’s ISODate constructor - and we need to compare them semantically rather than as strings. A date written as "2024-01-15T10:30:00.000Z" should match "2024-01-15T10:30:00Z" even though the strings differ. We normalize all dates to RFC3339 format in UTC:

case time.Time:

return v.UTC().Format(time.RFC3339)

MongoDB doesn’t guarantee document order in query results unless you explicitly sort. Even the order of fields within a document isn’t guaranteed in all contexts. This creates a fundamental problem for comparison: the same logically correct result might serialize differently between runs.

Consider a find() query that returns three documents. Run it once, you might get:

[

{ name: "Alice", age: 30 },

{ name: "Bob", age: 25 },

{ name: "Carol", age: 35 }

]

Run it again with the same data:

[

{ name: "Bob", age: 25 },

{ name: "Alice", age: 30 },

{ name: "Carol", age: 35 }

]

Both are correct results. A naive comparison would fail on the second run.

We solve this with unordered comparison as the default behavior. When comparing arrays, we don’t require elements to appear in the same position - we just require that for every element in the expected array, there’s a matching element somewhere in the actual array.

The algorithm selection is interesting. For simple arrays of primitive values (strings, numbers), we use frequency-based comparison:

func compareArraysByFrequency(expected, actual []interface{}, path string) Result {

expectedFreq := make(map[interface{}]int)

actualFreq := make(map[interface{}]int)

for _, item := range expected {

normalized := normalizePrimitive(item)

expectedFreq[normalized]++

}

for _, item := range actual {

normalized := normalizePrimitive(item)

actualFreq[normalized]++

}

// Compare frequencies

for key, expectedCount := range expectedFreq {

if actualCount := actualFreq[key]; actualCount != expectedCount {

return Result{IsMatch: false, ...}

}

}

return Result{IsMatch: true}

}

This is O(n) and handles duplicates correctly. An array with ["a", "a", "b"] won’t match ["a", "b", "b"] because the frequencies differ.

For arrays of objects, frequency counting doesn’t work - objects aren’t directly hashable, and two objects might be “equal” for our purposes even if they’re not identical (due to ignored fields, ellipsis patterns, etc.). Here we use backtracking:

func findMatching(expected, actual []interface{}, used []bool, expectedIndex int, ...) bool {

if expectedIndex >= len(expected) {

return true // All expected items found a match

}

for i := 0; i < len(actual); i++ {

if !used[i] {

result := compareValues(expected[expectedIndex], actual[i], ...)

if result.IsMatch {

used[i] = true

if findMatching(expected, actual, used, expectedIndex+1, ...) {

return true

}

used[i] = false // Backtrack

}

}

}

return false

}

This recursively tries to find a valid assignment of expected elements to actual elements. When it finds a match, it marks that actual element as “used” and recurses. If it hits a dead end, it backtracks and tries different assignments.

The worst case is O(n!) which sounds terrifying, but in practice documentation examples rarely have more than a handful of documents. We added a safety threshold: arrays larger than 50 elements automatically use ordered comparison to avoid runaway computation. Writers can also explicitly request ordered comparison when they know the output will be sorted:

Expect.that(result)

.withOrderedSort()

.shouldMatch(outputFilepath);

When unordered comparison fails, producing a helpful error message is tricky. We can’t just say “element 2 doesn’t match” because the elements don’t have stable positions. Instead, we analyze all pairings and report the closest matches:

func analyzeUnorderedMismatch(expected, actual []interface{}, ...) Result {

for expIdx, expDoc := range expected {

var bestMatch *matchResult

for actIdx, actDoc := range actual {

result := compareValues(expDoc, actDoc, ...)

// Track the match with fewest errors

if bestMatch == nil || len(result.Errors) < bestMatch.errorCount {

bestMatch = &matchResult{

actualIdx: actIdx,

result: result,

errorCount: len(result.Errors),

}

}

}

allMatches = append(allMatches, bestMatch)

}

// Build error message showing closest matches

}

The output shows which expected documents matched successfully and, for failures, which actual document was the closest match and what the differences were. This makes debugging much easier than a simple “comparison failed” message.

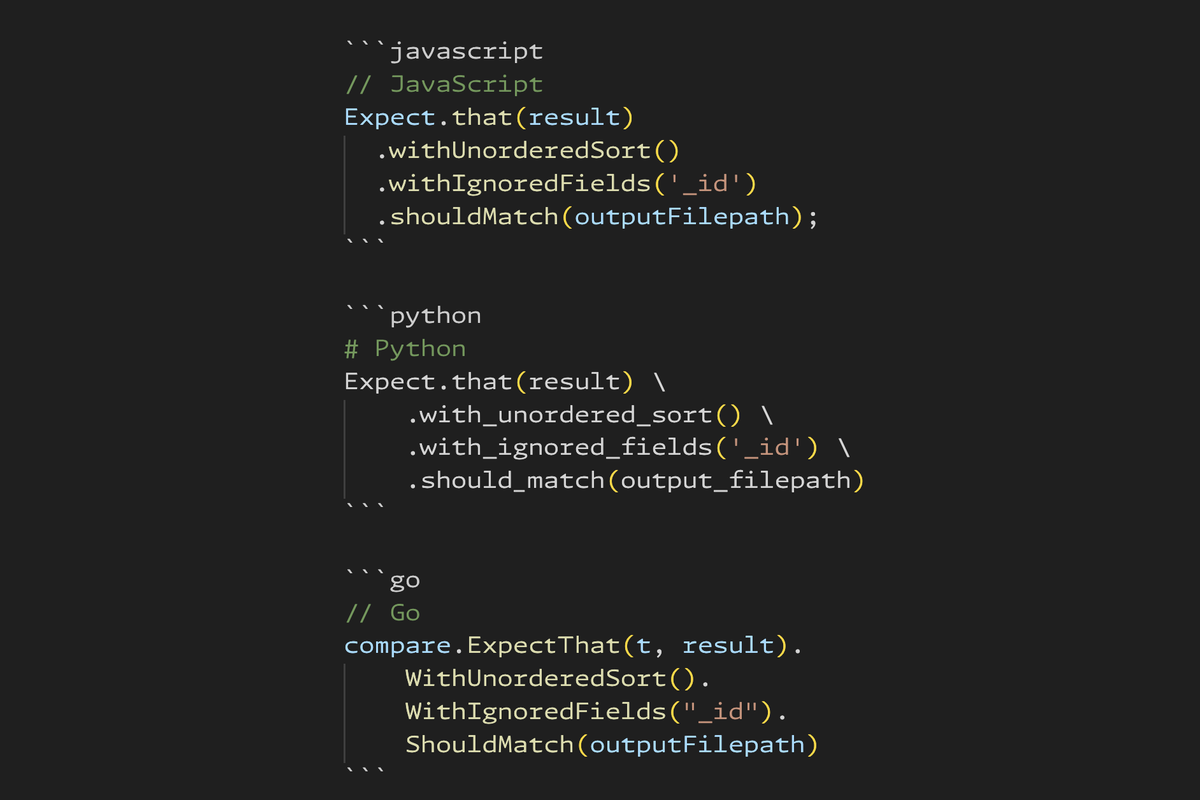

We maintain comparison utilities in six programming languages: JavaScript, Python, Go, C#, Java, and for MongoDB Shell (mongosh). Each language has its own idioms, conventions, and testing frameworks. But we wanted writers to have a consistent mental model when switching between doc sets.

The core insight was separating what writers need to express from how each language expresses it. Writers need to:

We standardized on a fluent builder pattern because it reads naturally and works across languages. Here’s how the same comparison looks in each:

// JavaScript

Expect.that(result)

.withUnorderedSort()

.withIgnoredFields('_id')

.shouldMatch(outputFilepath);

# Python

Expect.that(result) \

.with_unordered_sort() \

.with_ignored_fields('_id') \

.should_match(output_filepath)

// Go

compare.ExpectThat(t, result).

WithUnorderedSort().

WithIgnoredFields("_id").

ShouldMatch(outputFilepath)

// C#

Expect.That(result)

.WithUnorderedSort()

.WithIgnoredFields("_id")

.ShouldMatch(outputFilepath);

The pattern is the same everywhere: Expect.that(actual) → optional config methods → shouldMatch(expected). Method names follow each language’s conventions (camelCase vs snake_case vs PascalCase), but the structure is identical.

Go required one small adaptation: we pass the test context t as a parameter because Go’s testing framework needs it for failure reporting. But conceptually it’s the same API.

This consistency pays off in our documentation about the framework itself. We can write a single explanation of how comparison works, and writers can apply that knowledge regardless of which language they’re working in. The learning curve transfers across doc sets.

I mentioned earlier that writers can pass either a file path or inline expected values to shouldMatch(). This works because the comparison engine automatically detects what kind of content it’s receiving and routes to the appropriate comparison strategy.

The detection logic examines several characteristics:

static detectType(value, baseDir = null) {

if (typeof value === 'string') {

return this._detectStringType(value, baseDir);

}

if (Array.isArray(value)) {

return ContentType.ARRAY;

}

if (value && typeof value === 'object') {

return ContentType.OBJECT;

}

return ContentType.PRIMITIVE;

}

For strings, the analysis goes deeper:

static _detectStringType(str, baseDir) {

// Check if it's a file path (exists on filesystem)

if (this._isFilePath(str, baseDir)) {

return ContentType.FILE;

}

// Multi-line text takes priority

if (str.includes('\n') || str.includes('\r')) {

return ContentType.TEXT_BLOCK;

}

// Check for ellipsis patterns

if (this._containsEllipsisPattern(str)) {

return ContentType.PATTERN_STRING;

}

// Check for JSON-like syntax

if (this._looksLikeJSON(str)) {

return ContentType.STRUCTURED_STRING;

}

return ContentType.PLAIN_STRING;

}

Once we know what types we’re dealing with, we select a comparison strategy:

| Expected Type | Actual Type | Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| FILE | Any | Read file, parse, then compare |

| PATTERN_STRING | OBJECT/ARRAY | Parse pattern, compare with ellipsis handling |

| ARRAY/OBJECT | ARRAY/OBJECT | Direct structural comparison |

| TEXT_BLOCK | Any | Normalize whitespace, string compare |

| PRIMITIVE | PRIMITIVE | Direct equality |

The file path detection is smarter than a simple exists() check. Writers might run tests from different directories within the project, so we search for files relative to known landmarks:

func isFilePath(s string) bool {

// Direct path check

if _, err := os.Stat(s); err == nil {

return true

}

// Walk up directory tree to find 'driver' directory

wd, _ := os.Getwd()

for {

if base := filepath.Base(wd); base == "driver" {

candidate := filepath.Join(wd, s)

if _, err := os.Stat(candidate); err == nil {

return true

}

}

parent := filepath.Dir(wd)

if parent == wd {

break

}

wd = parent

}

return false

}

This means aggregation/filter/output.txt resolves correctly whether you run tests from the project root, from the tests directory, or from a nested test subdirectory.

The strategy pattern here is classic polymorphism: same external API, different internal behavior based on input characteristics. Writers don’t need to think about it - they just pass what they have, and the system figures out how to compare it.

Many of our code examples rely on MongoDB’s sample datasets - pre-built collections like sample_mflix (movies), sample_restaurants, and sample_analytics. These are great for tutorials because they provide realistic data without requiring writers to create elaborate test fixtures.

The problem: not everyone has these datasets loaded in their local MongoDB instance. A writer might be testing examples for a different doc set, or they might have just set up a fresh development environment. We didn’t want tests to fail in these cases - that would be noisy and confusing. We wanted them to skip gracefully with a clear message about what’s missing.

We built a dedicated utility that integrates with test frameworks. Writers use wrapper functions instead of writing detection logic themselves. At the test suite level:

import { describeWithSampleData } from '../utils/sampleDataChecker.js';

describeWithSampleData(

'Get Started example tests',

() => {

it('Should retrieve a movie matching the example output', async () => {

const result = await runGetStarted();

Expect.that(result).shouldMatch('get-started/get-started-output.sh');

});

},

'sample_mflix' // Required database

);

The describeWithSampleData wrapper checks for the specified database before running any tests in the suite. If sample_mflix isn’t available, the entire suite skips with a clear message.

For more granular control, writers can use itWithSampleData on individual tests:

describe('Movie tests', () => {

itWithSampleData('should filter movies by year', async () => {

// Test implementation

}, 'sample_mflix');

itWithSampleData('should find restaurants near theaters', async () => {

// Test implementation

}, ['sample_mflix', 'sample_restaurants']); // Multiple databases

});

Under the hood, the utility maintains a registry of standard sample databases and their expected collections:

const SAMPLE_DATABASES = {

sample_mflix: ['movies', 'theaters', 'users', 'comments', 'sessions'],

sample_restaurants: ['restaurants', 'neighborhoods'],

sample_analytics: ['customers', 'accounts', 'transactions'],

// ...

};

When checking availability, it verifies both that the database exists and that it contains the expected collections. This catches cases where someone has a database with the right name but incomplete data.

Results are cached to avoid repeated database queries during a test run. And on first use, the utility prints a summary showing which sample databases are available:

📊 Sample Data Status: 3 database(s) available

Found: sample_mflix, sample_restaurants, sample_analytics

The key insight is distinguishing between “this test failed because the code is wrong” and “this test couldn’t run because the environment isn’t set up.” The former is actionable feedback; the latter is just noise. By wrapping tests with declarative sample data requirements, we keep test output focused on actual problems while making the dependencies explicit and discoverable.

What started as a simple “compare two things” script evolved into a comprehensive comparison framework with type normalization, pattern matching, multiple comparison strategies, and careful attention to developer experience.

To reiterate, here’s where it started:

it('Should return filtered output that includes the three specified person records', async () => {

// Set up the database and run the code example

await loadFilterSampleData();

const result = await runFilterTutorial();

// Create a file that contains the output we show on the page.

// This is a change from hard-coding it in the page text

const outputFilepath = 'aggregation/pipelines/filter/tutorial-output.sh';

// Call the comparison script and expect the results to match

const arraysMatch = outputMatchesExampleOutput(outputFilepath, result);

expect(arraysMatch).toBe(true);

});

And here’s where we are currently:

describeWithSampleData(

'Get Started example tests',

() => {

it('Should retrieve a movie matching the example output', async () => {

const result = await runGetStarted();

Expect.that(result).shouldMatch('get-started/get-started-output.sh');

});

},

'sample_mflix' // Required database

);

The driving principle throughout was: writers shouldn’t need to think about comparison mechanics or learn language-specific testing implementation details. They should focus on whether the code example works and produces the right output. Everything else - the ellipsis parsing, the type coercion, the unordered matching - should just work.

Is it perfect? No. There are edge cases we haven’t handled, performance optimizations we could make, and probably some bugs lurking in the more exotic pattern combinations. But it’s working in production across six languages and hundreds of example files, catching real documentation errors and giving writers confidence that their examples are correct.

The next step is consolidating these six implementations into a single core library with language-specific wrappers. Right now, each language maintains its own version of the comparison logic, which means bug fixes and new features need to be implemented six times. A unified core would let us iterate faster and guarantee consistent behavior everywhere.

If you’re building documentation tooling for a multi-language project, I hope some of these patterns are useful. The specific problems are MongoDB-shaped, but the general approaches - fluent APIs, intelligent content detection, graceful degradation - apply broadly.

And if you’re a technical writer who’s been frustrated by the gap between “code that works when I run it manually” and “code that passes automated tests” - I hope this gives you a sense of what’s possible. The tooling can meet you where you are.