Upskilling in the AI Age

In which I answer someone who asked me how to get started with AI.

I’ve written before about why you should test the code examples in your documentation and why your docs team should write the code examples. I’ve even written about how to test them and what you should test compared to engineering tests. But I wrote that content through a very specific lens; as a member of a team of developers who happened to be writing documentation. My team was already conversant with developer testing frameworks, tooling, and testing practices.

Most documentation teams don’t have dedicated testing infrastructure.

Technical writers are plenty technical - they read code, understand APIs, write examples that demonstrate complex functionality. But they shouldn’t need to master a dozen different testing frameworks to validate that their code examples actually work.

When my team had the opportunity to establish official code example quality standards and processes for the organization, I realized we had a problem: we couldn’t just roll out the same tools we had been using to the entire documentation organization. We needed to build infrastructure that abstracts the testing complexity while giving contributors confidence their examples are correct.

So I present: the Grove Code Testing Framework.

When your product is code, developers need code examples to learn how to use your product. But code examples are worse than useless if they’re wrong. They mislead developers into thinking they have a solution, but instead waste developer time and erode trust in the product when the code doesn’t work. It’s unclear if the issue is the code example (disrespect for developer time) or the product itself is buggy (not trustworthy, don’t use it).

So there’s a minimum bar for entry: the code examples in documentation must meet three criteria:

They must meet this bar reliably. We must be able to replicate the results, so developers can replicate the results. And we must be able to execute them again when product versions change to expose any changes to APIs or functionality that did not get the appropriate updates in the docs.

My team used to use the actual developer tools to test the code examples we show in our SDK documentation. In my older blog post about how to test code examples, I show this example of using CMake and Catch2 to test the C++ SDK code examples I wrote for our docs:

TEST_CASE("Close a realm example", "[write]") {

auto relative_realm_path_directory = "open-close-realm/";

std::filesystem::create_directories(relative_realm_path_directory);

std::filesystem::path path =

std::filesystem::current_path().append(relative_realm_path_directory);

path = path.append("some");

path = path.replace_extension("realm");

// :snippet-start: close-realm-and-related-methods

// Create a database configuration.

auto config = realm::db_config();

config.set_path(path); // :remove:

auto realm = realm::db(config);

// Use the database...

// :remove-start:

auto dog = realm::Dog{.name = "Maui", .age = 3};

realm.write([&] { realm.add(std::move(dog)); });

auto managedDogs = realm.objects<realm::Dog>();

auto specificDog = managedDogs[0];

REQUIRE(specificDog.name == "Maui");

REQUIRE(specificDog.age == static_cast<long long>(3));

REQUIRE(managedDogs.size() == 1);

// :remove-end:

// ... later, close it.

// :snippet-start: close-realm

realm.close();

// :snippet-end:

// You can confirm that the database is closed if needed.

CHECK(realm.is_closed());

// Objects from the database become invalidated when you close the database.

CHECK(specificDog.is_invalidated());

// :snippet-end:

auto newDBInstance = realm::db(config);

auto sameDogsNewInstance = newDBInstance.objects<realm::Dog>();

auto anotherSpecificDog = sameDogsNewInstance[0];

REQUIRE(anotherSpecificDog.name == "Maui");

REQUIRE(sameDogsNewInstance.size() == 1);

newDBInstance.write([&] { newDBInstance.remove(anotherSpecificDog); });

auto managedDogsAfterDelete = newDBInstance.objects<realm::Dog>();

REQUIRE(managedDogsAfterDelete.size() == 0);

}

As you can see, that’s a lot of code, interspersed with markup and test assertions - in this case, CHECK and REQUIRE.

The problem with this approach is, it doesn’t scale. On my team, most of us writers knew one or maybe two programming languages and primarily worked in our respective test suites. That meant we might have to learn how to use one or two testing frameworks, one or two sets of assertions, etc. When the product that my team documents was deprecated, we supported 7 programming languages, one API, and one CLI.

But the company currently supports Drivers in 12 programming languages. There are ODMs and framework integrations. There’s a shell interface, a CLI, APIs, Kubernetes Operators, Terraform modules… the amount of code we must support is staggering.

The numbers tell the story: 40+ documentation projects, 35,000+ code examples, 40+ technical writers. Each writer might need to work across multiple languages depending on the product area. It just wasn’t realistic to ask everyone to learn the framework quirks, assertion syntax, and testing methodologies for a dozen programming languages.

What my team used to do couldn’t scale. So we needed a new approach.

The code I showed above interspersed examples and test assertions. If you’re a developer, you’re familiar with this from testing. But if you’re a technical writer who doesn’t regularly write engineering tests and use testing tools, it’s confusing to read. You have to think about what each line is doing and change context from our product functionality to framework idioms.

So my first thought to simplify this at scale was: separate the examples from the tests. Create the examples in runnable functions, and call those functions from test files. Most of our technical writers understand our products well enough to write code that shows usage, or can get hints from engineering when needed. So it’s a small step to wrap that in a function we can call from somewhere else.

The test function might look like this:

import { MongoClient } from 'mongodb';

// Instead of hard-coding a local writer's connection string,

// use an environment variable so we can abstract this for different environments

const uri = process.env.CONNECTION_STRING;

const client = new MongoClient(uri);

export async function runFilterTutorial() {

try {

const aggDB = client.db('agg_tutorials_db');

const persons = aggDB.collection('persons');

const pipeline = [];

// :snippet-start: match

pipeline.push({

$match: {

vocation: 'ENGINEER',

},

});

// :snippet-end:

// :snippet-start: sort

pipeline.push({

$sort: {

dateofbirth: -1,

},

});

// :snippet-end:

// :snippet-start: limit

pipeline.push({

$limit: 3,

});

// :snippet-end:

// :snippet-start: unset

pipeline.push({

$unset: ['_id', 'address'],

});

// :snippet-end:

// :snippet-start: run-pipeline

const aggregationResult = await persons.aggregate(pipeline);

// :snippet-end:

const documents = [];

for await (const document of aggregationResult) {

documents.push(document);

}

return documents;

} finally {

await client.close();

}

}

It’s a clean example. There are a couple of small changes from what a writer would normally do in manual testing:

snippet-start and snippet-end tags to specify which parts of the example we want to show in the docsrunFilterTutorial() instead of having a run() or main() declared in the file and executing the file directlyOtherwise, there’s nothing here that a writer won’t have seen or done already in their regular process of manually writing and testing code examples. It’s a small learning curve.

Part of the secret sauce of this system is writing the expected output to a file. We can refer to this file to show the output in our documentation, and our system validates that when we run the example we saw above, it produces this output. So we always know that the output we show in the docs is the actual output produced by this example.

Currently, we expect writers to console log the function call results and save this to an output file. In the future, we could potentially automate this step or otherwise improve it. This is already familiar to our writers; they already expect to manually test the example and have some expectation of what output it should produce. We’re just asking them to capture it to a file.

{

person_id: '7363626383',

firstname: 'Carl',

lastname: 'Simmons',

dateofbirth: 1998-12-26T13:13:55.000Z,

vocation: 'ENGINEER'

}

{

person_id: '1723338115',

firstname: 'Olive',

lastname: 'Ranieri',

dateofbirth: 1985-05-12T23:14:30.000Z,

gender: 'FEMALE',

vocation: 'ENGINEER'

}

{

person_id: '6392529400',

firstname: 'Elise',

lastname: 'Smith',

dateofbirth: 1972-01-13T09:32:07.000Z,

vocation: 'ENGINEER'

}

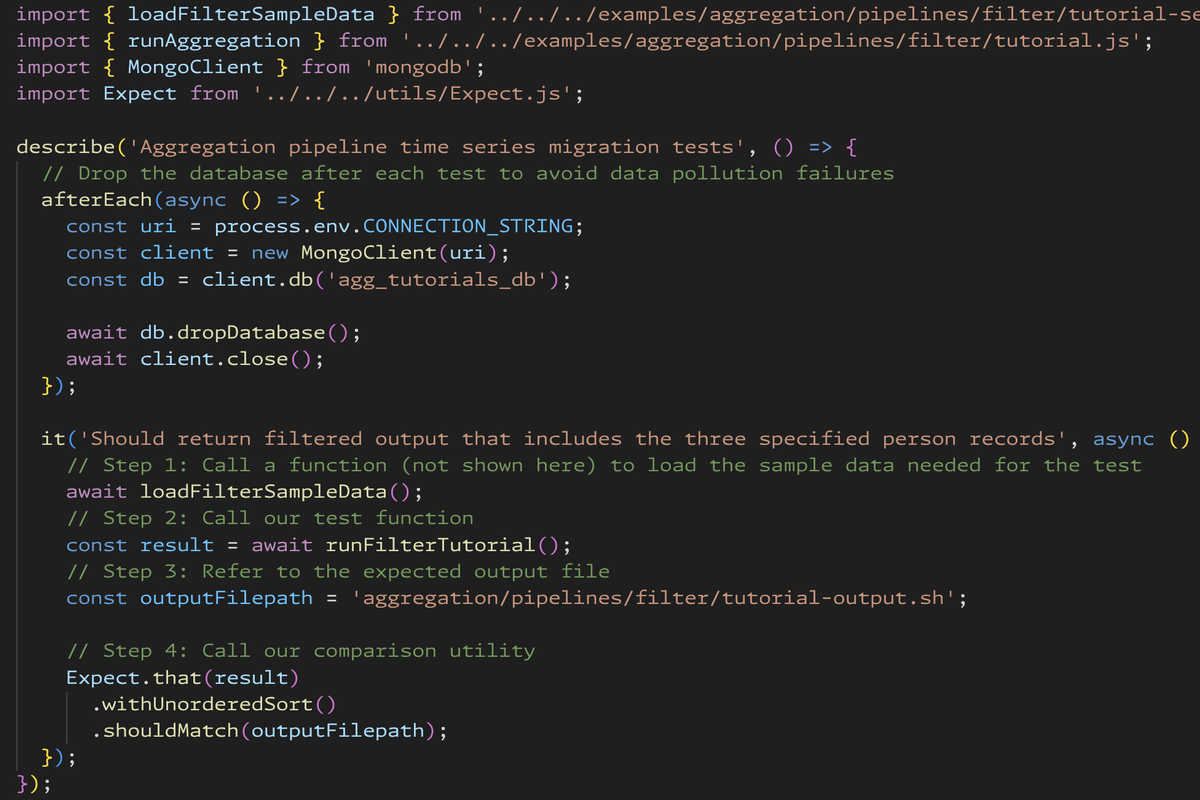

The other piece of this equation is brand new to most writers: the test. Again, my goal was to make Grove as simple as possible so it could scale across teams that do not regularly work in code example test infrastructure. So here’s what Grove test files look like:

import { loadFilterSampleData } from '../../../examples/aggregation/pipelines/filter/tutorial-setup.js';

import { runAggregation } from '../../../examples/aggregation/pipelines/filter/tutorial.js';

import { MongoClient } from 'mongodb';

import Expect from '../../../utils/Expect.js';

describe('Aggregation pipeline time series migration tests', () => {

// Drop the database after each test to avoid data pollution failures

afterEach(async () => {

const uri = process.env.CONNECTION_STRING;

const client = new MongoClient(uri);

const db = client.db('agg_tutorials_db');

await db.dropDatabase();

await client.close();

});

it('Should return filtered output that includes the three specified person records', async () => {

// Step 1: Call a function (not shown here) to load the sample data needed for the test

await loadFilterSampleData();

// Step 2: Call our test function

const result = await runFilterTutorial();

// Step 3: Refer to the expected output file

const outputFilepath = 'aggregation/pipelines/filter/tutorial-output.sh';

// Step 4: Call our comparison utility

Expect.that(result)

.withUnorderedSort()

.shouldMatch(outputFilepath);

});

});

We expose some of the innards of the test framework here - we’re asking writers to:

But realistically, that seems like a very small subset of test functionality to master.

The secret sauce is in this function call:

Expect.that(result)

.withUnorderedSort()

.shouldMatch(outputFilepath);

I’m going to write a separate in-depth article about the comparison library because there’s a lot happening under the covers. It handles ordered and unordered matching, field ignoring for dynamic values like ObjectIds and timestamps, MongoDB type coercion (Decimal128, Date, ObjectId), and truncation for large outputs - all abstracted behind that single fluent API. But the key takeaway for this article is that it’s one conceptual pattern to learn that abstracts away all of the test functionality. The function signature reads like English and describes clearly what it’s doing:

(We had a lengthy debate about whether that should be .shouldMatchFileContents() or something more explicit, but optimized for short because it should be easy enough for writers to intuit what it means.)

An even cooler thing is that this also works:

it('Should return the expected bucket settings after creating the collection', async () => {

// ...setup code here...

const actualSettings = await weatherBucket.options();

const expectedSettings = {

timeseries: {

timeField: 'time',

metaField: 'sensor',

bucketMaxSpanSeconds: 3600,

bucketRoundingSeconds: 3600,

},

expireAfterSeconds: 86400,

};

Expect.that(actualSettings)

.shouldMatch(expectedSettings)

});

If we don’t need to show the output in the docs, we can declare the expected output inline and pass that to the same API. Writer’s don’t have to learn a separate API.

Remember how I mentioned that we support Drivers in 12 programming languages?

A key design goal for Grove was keeping the API conceptually unified across languages. Writers shouldn’t need to learn entirely different patterns when switching between documentation sets. So the same Grove comparison API looks like this in C#:

Expect.That(results)

.ShouldMatch(outputFilepath);

Or like this in Go:

compare.ExpectThat(t, result).ShouldMatch(expectedOutputFilepath)

Or like this in Python:

Expect.that(result).should_match(output_filepath)

While the syntax may change slightly to account for differences in programming language, it’s the same API for writers to use everywhere. It abstracts away every key/value pair check into some pretty cool stuff inside our comparison utility.

Grove isn’t just for local development. I’ve set up CI to run all the tests when:

This ensures that the test didn’t just pass once five years ago. It continues to pass as product versions and external dependencies evolve. This helps us catch entire categories of failures:

Even with simplified tooling, contributors weren’t going to magically start using this infrastructure in a vacuum. Documentation contributors all have different baseline familiarity with testing frameworks. We had to create enablement resources to meet people where they are.

I started with a small cross-functional working group of early adopters as my UAT group. I incorporated their feedback into additional enhancements to simplify the tooling and test infrastructure.

Then, I wrote docs based on the challenges I watched our UAT group struggle with. The docs walk contributors through performing these steps in each of the programming languages we currently support:

I’ve also run some workshops on using the new tooling, and have provided one-on-one troubleshooting and mentorship for writers as they work on their first few PRs that use our tools. And finally, I’m advocating for permanent training resources that will become part of our standard writer onboarding.

Grove now serves 40+ documentation projects with 400+ tested code examples across 6 programming languages. In the next article, I’ll zoom in on the comparison library - the problems we had to solve to make that fluent API work across languages with different type systems, different collection semantics, and different testing idioms. Spoiler alert: it’s bigger on the inside.