Agent-Friendly Docs

In which I ask an agent to view hundreds of docs pages - and feel sad.

My wife has been using a word-diffing tool called dwdiff for years. It’s a ~25-year-old C program. Neither of us writes C. She made an attempt to understand it many years ago and port it to some other language she works in more regularly, but never finished the job. When she commented on using it in a pipeline with another Go tool I had written for her, I thought: “How hard could it be to make a modern version of this in Go?”

Two libraries and a lot of algorithm spelunking later, I have an answer: harder than you’d think, but for interesting reasons.

Traditional diff tools like diff and git diff operate at the line level. When a single word changes on a line, the entire line shows up as deleted and re-added. For comparing prose, documentation, or code where you want to see exactly what changed within a line, this is suboptimal.

Word-based diff tools like wdiff and dwdiff improve on this by tokenizing text into words and comparing at that level. But there’s a subtlety that many word-diff implementations miss: delimiter handling.

Consider comparing these two lines of code:

void someFunction(SomeType var)

void someFunction(SomeOtherType var)

A naive word-differ that splits only on whitespace would report that someFunction(SomeType changed to someFunction(SomeOtherType — grouping the function name with the parameter type because the parenthesis isn’t treated as a word boundary.

What I wanted was a tool that:

(, ), {, } are treated as separate tokensThat third criterion turned out to be the hard part.

My first approach was straightforward: port the C-based dwdiff to Go. I created go-dwdiff (which I’ve since deleted) and started translating. I thought it might be a relatively trivial wrapper around an existing Go diff library, and proceeded with that approach.

The obvious choice was go-diff, a popular Go implementation of the Myers O(ND) diff algorithm. I already use it in another Go tool I wrote, and it’s a pretty popular and reasonably maintained Go library. I hooked it up, got the tokenization working, and… the output was wrong. Not incorrect — it correctly identified what was deleted and inserted — but unreadable.

The Myers algorithm, published in 1986, finds the mathematically optimal edit sequence between two texts — the minimum number of insertions and deletions needed to transform one into the other. This is great for source control and patches, but it has a problem for human-readable output: it doesn’t care about semantic coherence.

When common words like “the”, “for”, “-”, or “with” appear in both the deleted and inserted content, Myers happily uses them as anchor points, fragmenting the output in ways that make no sense to humans.

Here’s a real example from my testing. I was diffing two versions of a README file and got output like:

+Fenestra supports a TOML configuration file following the background. [XDG Base Directory]...

The word “background” came from a completely different sentence (“windows run independently in the background”) and got attached to the wrong context. The diff was mathematically optimal but semantically nonsensical.

Another example — two separate headings merged into one incoherent line:

+### Wails v2 Limitation Example config.toml

The original dwdiff uses GNU diff, which includes heuristics specifically designed to avoid this fragmentation. GNU diff has decades of refinement in discard_confusing_lines() and shift_boundaries() — preprocessing and postprocessing steps that make output more readable.

But there’s a problem: GNU diff is GPL-licensed. I wanted my tools to be MIT-licensed so they could be used freely in a broad range of projects. Porting GNU diff’s algorithm would mean either accepting the GPL or carefully reimplementing without copying — and the algorithm is complex enough that this distinction gets murky.

I explored several other options:

| Algorithm | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Myers (go-diff) | Fast, optimal edit distance, well-understood | Fragments output on common words |

| Patience Diff | Better semantic grouping, uses unique lines as anchors | Designed for line-level diff, not tokens |

| GNU Diff | Excellent heuristics for readability | GPL license |

| DiffCleanupSemantic (go-diff) | Eliminates trivial equalities | Too aggressive — eliminates ALL anchors |

I tried go-diff’s DiffCleanupSemantic() function, hoping it would clean up the fragmented output. Instead, it was too aggressive — it eliminated all anchor points and produced one giant delete block followed by one giant insert block. Not helpful.

I also tried various preprocessing approaches: filtering high-frequency tokens, using stopword lists, adjusting thresholds. Each fix broke something else. Lower the threshold to filter common words, and you accidentally filter legitimate matches. Raise it, and you get fragmentation.

The fundamental issue was that I was trying to fix the output of an algorithm that wasn’t designed for human readability. The fix needed to be in the algorithm itself.

After extensive experimentation, I concluded I needed to build my own diffing library from scratch — one designed from the ground up to produce readable output rather than optimal edit distance.

The result is two libraries:

diffx is a Go diffing library implementing Myers O(ND) with heuristics specifically designed for human-readable output. Rather than optimizing for minimal edit distance, it prioritizes semantic clarity.

Key features:

tokendiff builds on diffx to provide word-level diffing with delimiter support. It handles tokenization, formatting, and the CLI interface.

Key features:

(){}[] are treated as separate tokensfoo(bar) shouldn’t become foo ( bar )git diff outputFor simple cases (files up to ~15 lines), tokendiff produces output identical to the original dwdiff. For larger files, the output differs in grouping but is typically more readable because the histogram algorithm avoids the fragmentation issues.

# Simple case - identical output

echo "hello world" > /tmp/a.txt && echo "hello there world" > /tmp/b.txt

tokendiff /tmp/a.txt /tmp/b.txt

# Output: hello {+there+} world

# Same as dwdiff

dwdiff /tmp/a.txt /tmp/b.txt

# Output: hello {+there+} world

For complex cases with many structural changes, tokendiff groups changes more cohesively. Where dwdiff (and Myers-based tools) might produce:

- The

+ A

quick

- brown

+ red

fox

tokendiff produces:

- The quick brown

+ A quick red

fox

Both are correct, but the grouped version is easier for humans to parse.

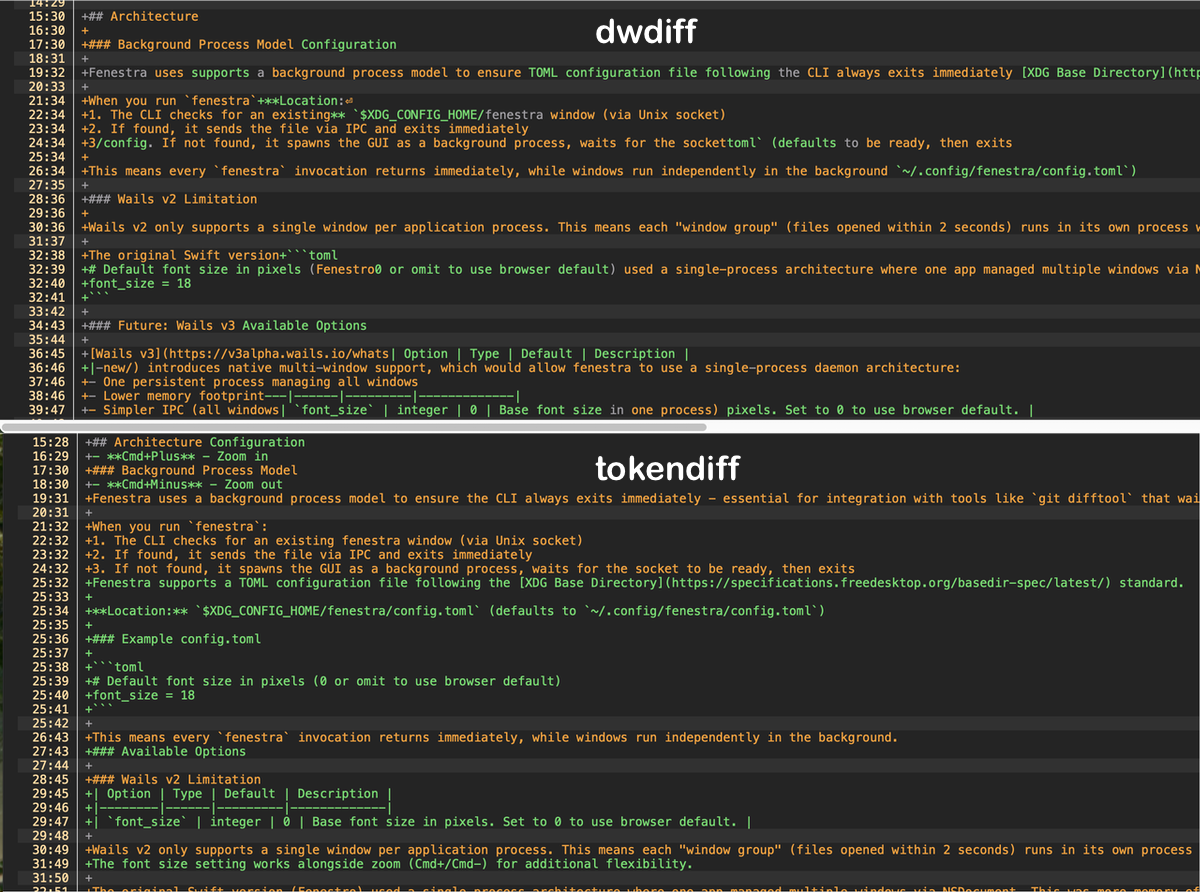

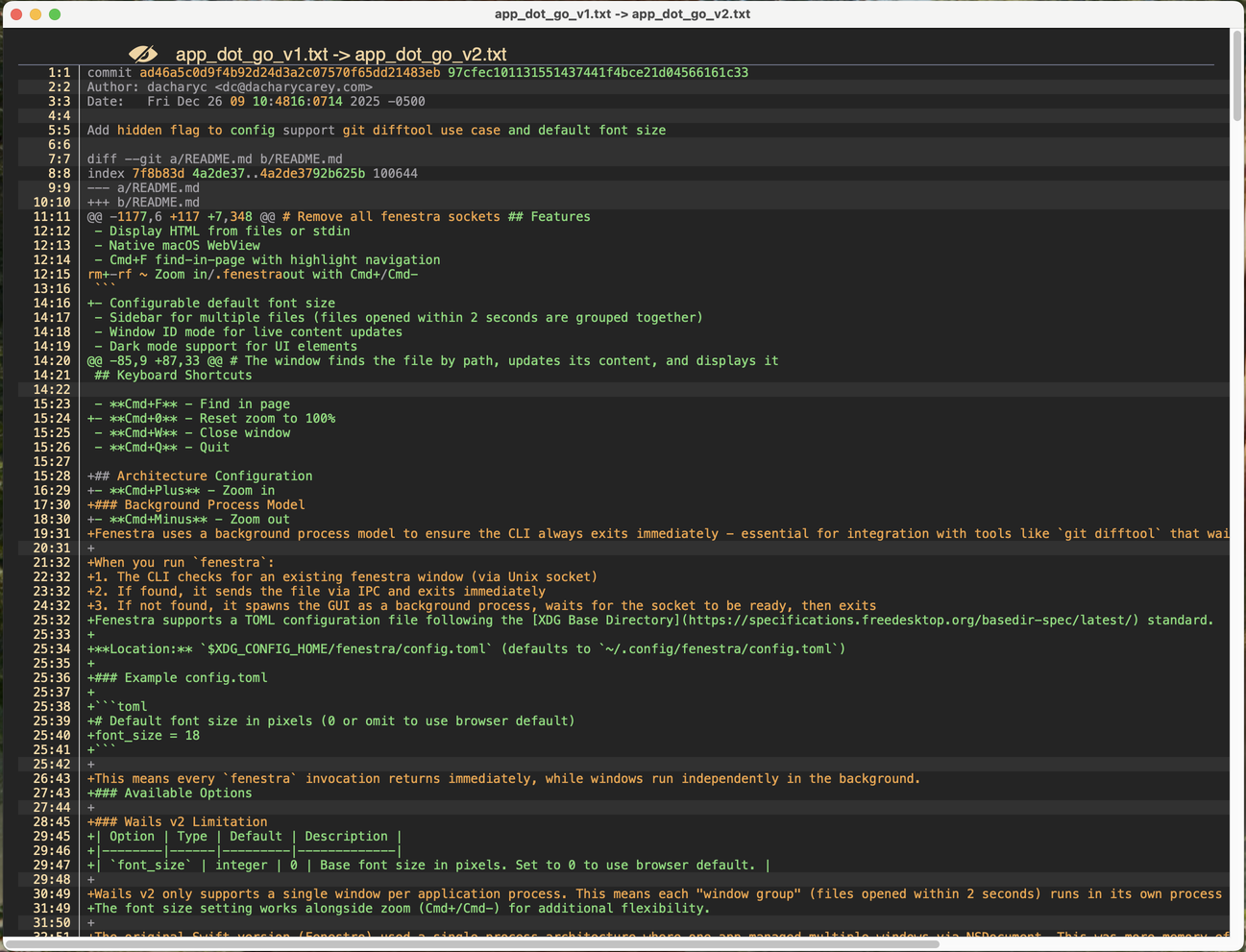

This image is a screenshot of dwdiff output for a diff I used in testing. It’s good but highlights some of the issues with even the GNU algorithm:

- Zoom in as an insert operation, interleaved with /.fenestra as a delete operation (with no spacing), interleved with out with Cmd+/Cmd- as an insert operation (also with no spacing)### Background Process Model as a delete operation, followed by Configuration as an insert operation. This is the wrong pairing - Configuration was actually an insert on line 15:30 replacing the deleted Architecture in the H2.Fenestra shows as an equality operation (unchanged), followed by uses as delete, then supports as insert, then a as equality, etc. These are actually two different lines, but the diffing algorithm is trying to interpret them as the same line.

There are other issues there that make it difficult to follow, including the interleaving of the deleted Future: Wails v3 section and the table describing the available configuration options.

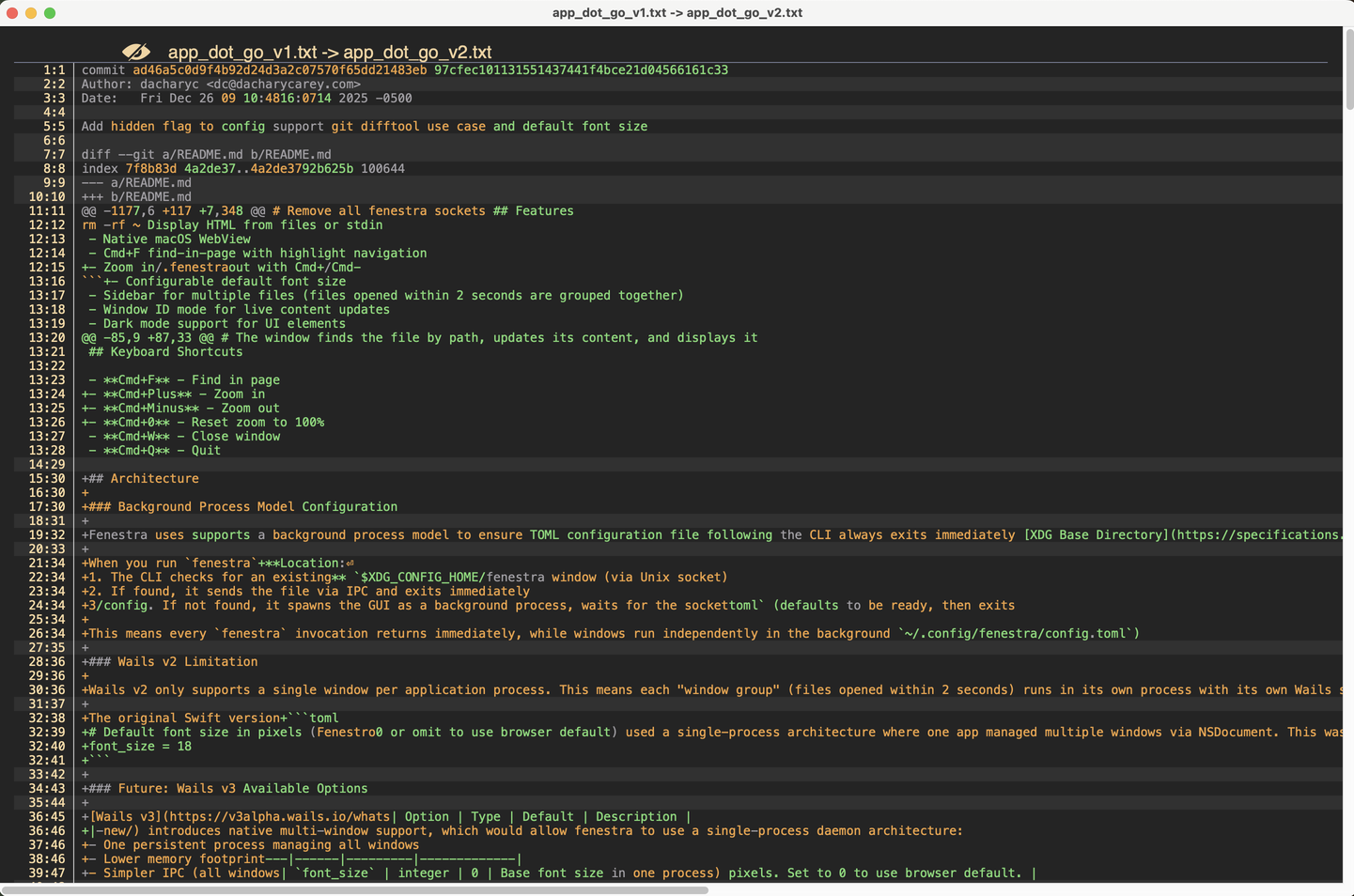

This image is a screenshot of tokendiff output for the same diff used in testing. It improves the semantic groupings, making it more readable and easier for humans to understand. It still has some of the same interleaving issues as dwdiff, but overall I think I prefer the tokendiff output:

- Zoom in as an insert operation, interleaved with /.fenestra as a delete operation (with no spacing), interleved with out with Cmd+/Cmd- as an insert operation (also with no spacing)tokendiff correctly pairs the removed Architecture delete operation with the inserted Configuration operation in the H2tokendiff optimizes for a longer contiguous delete block instead of interpreting it as the “same” line with changes in dwdiff, making it easier to understand that it and the following lines were deleted and the lines starting at 25:32 were inserted.

Notably, tokendiff keeps the toml code example block intact, as well as the table content, making key contextual elements in the diff easier to read and understand.

Now let’s get into the algorithmic details. This section covers what I learned about diff algorithms, the concepts that informed my implementations, and what I had to figure out independently.

The foundation of most diff algorithms is Eugene Myers’ 1986 paper, “An O(ND) Difference Algorithm and Its Variations”. The key insight is representing the diff problem as finding a shortest path through an edit graph.

Given two sequences A and B:

The shortest path from (0,0) to (len(A), len(B)) with the fewest non-diagonal moves is the minimal edit script.

Myers’ algorithm finds this path using a clever breadth-first search that tracks the frontier of positions reachable with D edits (where D = 0, 1, 2, …). The key optimization is that when you find a diagonal (matching elements), you can extend it greedily since diagonals don’t increase the edit count.

diffx implements this with bidirectional search: a forward pass from (0,0) and a backward pass from (n,m) simultaneously. When the passes meet, you’ve found the “middle snake” — the optimal split point for divide-and-conquer.

Myers finds the optimal edit sequence, but “optimal” means minimum edits, not maximum readability. Consider:

Old: ["The", "quick", "brown", "fox", "jumps"]

New: ["A", "slow", "red", "fox", "leaps"]

Myers might produce:

Delete: The Insert: A

Equal: quick (spurious match if both texts have "quick")

Delete: brown Insert: slow red

Equal: fox

Delete: jumps Insert: leaps

If both texts contain “quick” somewhere, Myers will anchor on it even if it appears in completely different semantic contexts. The algorithm has no concept of where in the sentence a word appears or what it means.

The histogram algorithm (a concept used in Git and documented in libraries like imara-diff) takes a different approach: instead of using any matching element as an anchor, it selects low-frequency elements. My implementation of this concept includes original additions like position-balanced anchor scoring.

The intuition is that rare words are more semantically significant. If “authentication” appears once in each file, it’s probably the same authentication block. If “the” appears 50 times in each file, matching on it tells you nothing useful.

Algorithm:

This naturally avoids common words without needing an explicit stopword list (though diffx uses one for additional filtering).

Before running the core algorithm, diffx classifies elements:

The threshold is dynamic: 5 + (len(a)+len(b))/64 (minimum 8). This scales with input size — larger files can tolerate more repeats before an element is considered “confusing.”

Provisional elements are kept only if they’re anchored by kept elements on both sides. This prevents filtering out legitimate matches while still removing noise.

Critical implementation detail: After diffing the filtered sequences, results must be mapped back to original indices. This requires expanding Equal operations element-by-element to handle interleaved filtered elements. Getting this wrong causes off-by-one errors that cascade through the output.

After the diff is computed, boundaries are shifted to align with logical breaks. GNU diff has a concept called shift_boundaries() that does something similar, but my implementation takes a different approach: instead of fixed rules, it uses a scoring system to find optimal boundary positions.

Scoring heuristics:

blankLineBonus = 10 — Keep blank lines as separatorsstartOfLineBonus = 3 — Align with sequence startendOfLineBonus = 3 — Align with sequence endpunctuationBonus = 2 — Align at punctuationFor Delete/Insert operations where identical elements repeat, the algorithm tries shifting forward and backward, choosing the best-scored position. This turns:

Equal: ["foo", "bar"]

Delete: ["bar"]

Insert: ["bar", "baz"]

Into:

Equal: ["foo", "bar"]

Insert: ["baz"]

One issue I discovered empirically: single-token Equal regions for stopwords (articles, prepositions) sandwiched between changes create visual noise without aiding comprehension.

Example output without stopword handling:

Delete: essential Insert: Display

Equal: for

Delete: integration Insert: files

The “for” isn’t really a meaningful anchor — it’s just a common word that happened to appear in both contexts.

Solution: diffx maintains a stopword list and can eliminate these weak anchors by converting them to Delete+Insert pairs:

var stopwords = map[string]bool{

"-": true, ".": true, ",": true,

"a": true, "an": true, "the": true,

"to": true, "of": true, "in": true,

"for": true, "and": true, "or": true,

// ... etc

}

But this has to be done carefully. Naive elimination breaks position tracking because tokendiff uses byte positions to extract original text for spacing reconstruction. Reordering tokens after positions are assigned causes markers to appear in wrong places.

The fix is doing stopword elimination at the algorithm level (before positions are assigned), not as a postprocessing step.

One subtle problem with word-level diff: how do you reconstruct spacing in the output?

Given foo(bar), you don’t want foo ( bar ). But given foo bar, you do want foo bar.

tokendiff uses heuristics for this:

// Don't add space before: ) ] } > punctuation , . : ; ! ?

func NeedsSpaceBefore(token string) bool {

if len(token) == 0 {

return false

}

first := []rune(token)[0]

return !strings.ContainsRune(")]}>,.;:!?/\\", first)

}

// Don't add space after: ( [ { < path separators

func NeedsSpaceAfter(token string) bool {

if len(token) == 0 {

return false

}

last := []rune(token)[len(token)-1]

return !strings.ContainsRune("([{</\\.", last)

}

An important distinction: diffx and tokendiff are original implementations, not ports or translations of existing code. They’re informed by academic papers and reference implementations, but the code is written from scratch.

| Component | Concept Source | What I Did Differently |

|---|---|---|

| Myers algorithm | Myers 1986 paper | Clean-room implementation with original heuristics (significant match tracking, custom cost limits) |

| Bidirectional search | Myers paper Section 4b | Standard approach, but with novel fallback scoring when search exceeds cost limits |

| Histogram anchor selection | Git, imara-diff concepts | Original implementation with position-balanced scoring and explicit stopword filtering |

| Element filtering | Neil Fraser’s writings | Original three-tier classification system (keep/discard/provisional) with adaptive thresholds |

| Boundary shifting | GNU diff concept | Completely different approach: scoring-based optimization instead of fixed rules |

| Tokenization | dwdiff concept | Original Go implementation with UTF-8 support and position tracking |

| Output formatting | Original | Novel spacing heuristics and state machine for marker placement |

The code cites its conceptual sources in comments — for example, tokendiff’s preprocessing notes it’s “inspired by GNU diff’s discard_confusing_lines” — but the implementations are independent. This matters for licensing: there’s no GPL code in either library, and both are MIT-licensed.

Why I couldn’t just use existing code:

I initially tried to put everything in one library, but the concerns are genuinely separate:

diffx is about comparing arbitrary sequences of elements. It doesn’t know or care that those elements are words. It just needs things with Hash() and Equal() methods.

tokendiff is about word-level diffing of text. It handles tokenization (what is a word? what is a delimiter?), formatting (markers, colors, line numbers), and text reconstruction (spacing, original positions).

Separating them means diffx can be used for other sequence-comparison problems: AST nodes, database rows, anything that can be hashed and compared. And tokendiff could theoretically swap in a different diff engine if a better one came along.

diffx is optimized for quality over raw speed, but it’s still fast:

| Input Size | Typical Time | In Practice |

|---|---|---|

| 5 elements | ~1µs | Essentially instantaneous; could run 1 million times per second |

| 100 elements | ~20µs | Still imperceptible; 50,000 operations per second |

| 1000 elements | ~400µs | Under half a millisecond; 2,500 operations per second |

(For reference: µs is microseconds, or one millionth of a second. ms is milliseconds, or one thousandth of a second.)

The histogram algorithm adds overhead compared to pure Myers, but it’s typically faster than character-based diff libraries because it operates at the element level.

tokendiff adds tokenization overhead (~2.5µs per call) plus formatting. End-to-end for typical source files (few hundred tokens), expect 10-20µs — still well under a millisecond.

Optimal edit distance ≠ readable output. The mathematically best diff can be the worst for humans to understand. Design for your actual use case.

Preprocessing and postprocessing matter as much as the core algorithm. GNU diff’s readability comes from decades of heuristic refinement, not just Myers.

Frequency-based anchor selection is powerful. Low-frequency elements are inherently more meaningful as anchors. The histogram algorithm leverages this naturally.

Token position tracking is subtle. Any transformation that reorders tokens must update position mappings, or formatting breaks. I learned this the hard way.

License constraints drive architecture. I might have saved time porting GNU diff, but the GPL constraint forced me to understand the problem deeply enough to solve it independently.

What started as “port this C tool to Go” became a deep dive into diff algorithms and the gap between mathematical optimality and human readability. The result is a pair of libraries that solve the original problem and might be useful for others facing similar challenges.

If you need word-level diffs with readable output, check out:

And if you want to go deeper, the original references are worth reading: