Inside the Code Example Comparison APIs

In which I deep dive into the problem domain to discuss the problems we had to solve.

After a months-long code example audit process that included:

We had enough information to start drawing conclusions from the audit.

I did a preliminary share-out of some findings as a ~20 minute talk, but the real artifact of this process was the audit report. I wrote an 88-page report that included:

While the specifics are proprietary to our org, I can share some general findings that I hope can help shape how we think about code examples in developer documentation across the industry.

Data in a void is meaningless. You need some idea of what questions you want to answer in order to draw meaningful conclusions from data.

My org had never attempted to audit code examples in this way before. We didn’t know exactly what we wanted to learn from this audit. At a high level, the objective was to better understand our code example distribution across types, programming languages, and product coverage in order to identify gaps and scope work to fill them. But I took this audit as an opportunity to explore of our code example coverage, as we have historically taken a very ad-hoc approach to code examples. Finally, we had an excuse and scope to try to understand this important facet of our documentation in a more holistic way.

When your product is code, code examples are the guide to your product. There is no GUI for SDKs and drivers. The code examples in your documentation form the basis for how developers discover and learn to use your product.

To help us understand our code example landscape better, I formulated these research questions:

One of the gaps we wondered about is whether we had “enough” code example coverage in any given programming language. The data we had could tell us:

But to truly answer this question, we needed additional business intelligence that wasn’t covered by our audit database. We needed to know:

As I dug deeper, I realized we still didn’t have the information required to answer this question in a comprehensive way that is most meaningful to our business.

Even a relatively simple question like “which programming languages are most important to us as an org” doesn’t necessarily have a simple answer. There are many ways we could slice this question. What makes a given programming language important to us? It might be:

If I were to try to figure out, say, the top 3 programming languages for each of those facets, I might get very different answers. And in an org the size of mine, it’s not simple to find the answers. The data I would need to answer those questions could be scattered across many different systems (support ticketing system, feedback tracking system, analytics system, etc.), some of which I don’t have access to (revenue details, new workload analysis, key industry targets), and could have dozens of different stakeholders I would need to find and query to try to get answers.

So, I settled for hand-wavey proxies, but would like to explore this in more detail if we start doing regular (annual) audits.

To try to come up with some answer that could guide our work to improve coverage in the next 12 months, I honed in on two areas I could potentially use as proxies for the real business intelligence I lack in order to assess our existing coverage:

To determine what we should consider the “key programming languages,” I referred to two developer surveys:

I did some math to omit languages that aren’t relevant to our product, and cross-reference languages used by developer roles that are most likely to use our product, and came up with a list of the top 5 programming languages that are most relevant to us. Once I had this list, I could focus on coverage in these programming languages and categories.

The list made me start to consider the developer personas who may use our product. I realized something we rarely talk about is how our code examples break down by operations/DevOps doing configuration and infrastructure-related tasks versus developers who are building software that uses our products and features. So I started looking at developer personas.

When I mapped code examples to these two developer personas, omitting examples whose metadata may be skewed by bad data, I realized we provide more coverage for programmatic configuration tasks (operations/DevOps) than we do for developers who write software using our products. So the developer languages are underrepresented.

This is consistent with user feedback we get in our annual reports requesting “more code examples.” The people making these requests are developers who are building with our products who are underserved by our code examples. But now we have the ability to map data points to these requests.

In addition to consistently getting requests for “more code examples” in our user feedback, we regularly get requests for “more complex” or “more real-world” code examples. Without more data around this, it’s difficult to take action. So I wanted to try to understand how we might break down “complexity” and identify areas where we needed “more complex” code examples.

For this initial audit, I used code example length as a proxy for “complexity” or “real-world usage.” I performed analysis across these two categories:

I found, to my surprise, that a large percentage of the code blocks in our documentation are one-line code blocks. The number seemed high to me, so I started to dig into what we might conclude about these examples. Is it inherently bad that a code block is one line? Do we need to take some action around this?

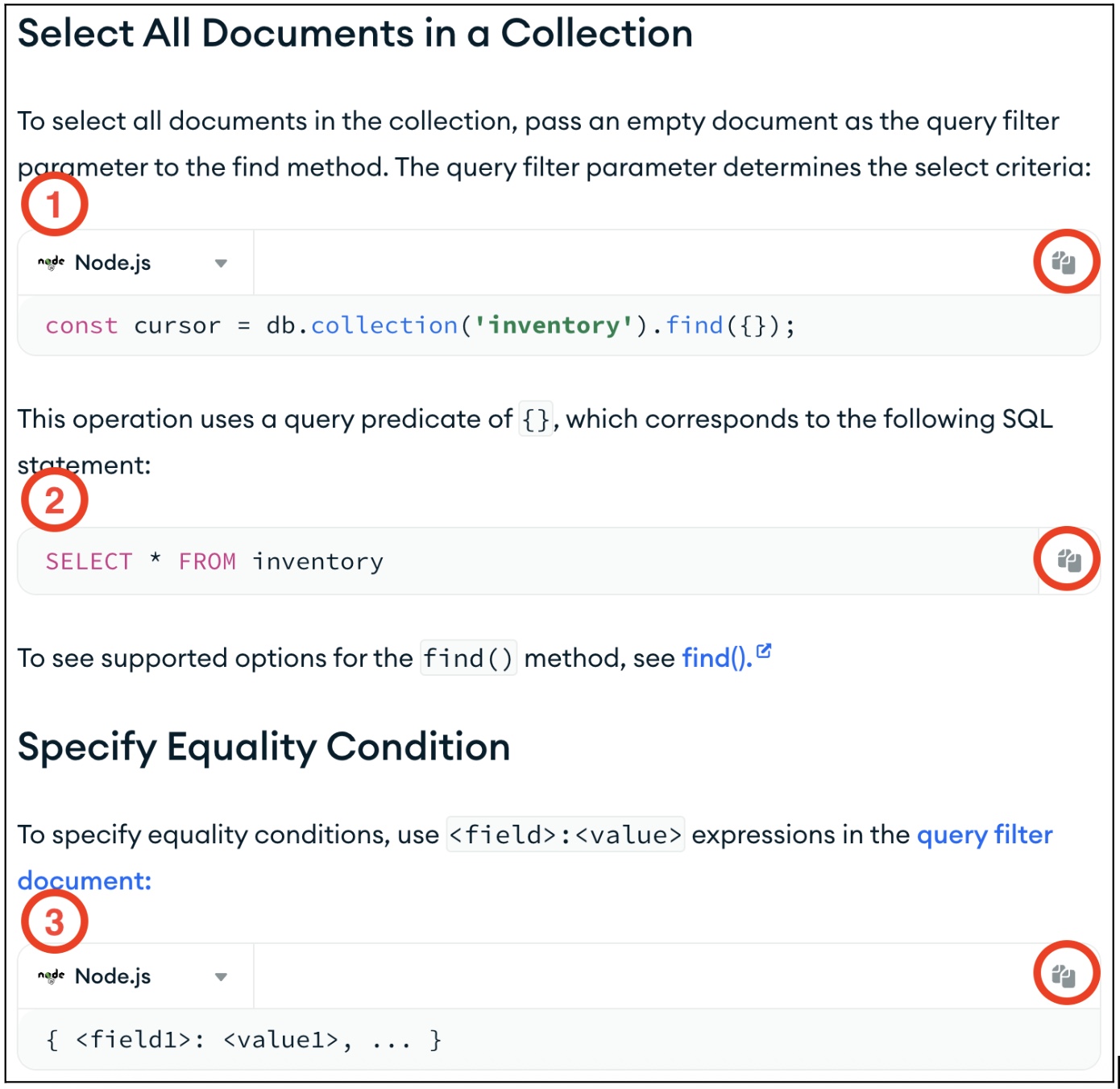

To illustrate some of the considerations around one-line code blocks, consider this section from one of our documentation pages:

Each one-liner in this part of the page has varying reasons to treat it differently. In some cases, we may not want to count these or render them as code blocks in our docs page HTML:

This is a code example of the Syntax Example type that illustrates caling a find() method with an empty filter to work with all documents in a collection. The clipboard icon on the right indicates that the code is copyable, and implies the developer may want to use this code directly in their application.

However, this method call uses a specific collection name, inventory, which is unlikely to apply to the developer’s use case. It also lacks the larger context, such as any error handling that may be required in the event that the db.collection() call fails, or performing any action with the returned result, such as iterating.

A developer is unlikely to copy this code block directly to their application; they are more likely to insert their own db.collection() call in their IDE in the context where it makes sense. In this case, the information provides value as a syntax example, but should not necessarily indicate that we expect a developer to do anything directly with this code block. Arguably, this example should not be copyable, as it serves primarily as a visible reference to illustrate the syntax.

This code block illustrates the SQL equivalent that corresponds to our query syntax, for developers coming from a relational background who may need to translate their prior syntax to our query paradigms. However, there is no scenario where this SQL line needs to be copyable.

Additionally, we don’t want to imply to web crawlers or LLMs that this is a code example demonstrating our product usage. This type of code example should have a different display paradigm and should not be rendered using the HTML <code> tag. It has informational value, but should not be treated the same as and counted as one of our company’s code blocks.

This is a more abstract syntax example that only contains placeholders. It has informational value because it demonstrates the structure of a query filter, but has no value as a copyable code block. This type of code example should have a different display paradigm and should not be rendered using the HTML <code> tag. It has informational value, but should not be treated the same as and counted as one of our company’s code blocks.

I have concluded that we need to develop better standards around when a code block should be copyable, and plan to work with our UX team to provide ways to distinguish between informational and actionable code examples on a page, both visually for human readers and in HTML markup for web crawlers and LLMs.

With more digging, I also discovered that only 2 of our company’s ~40 documentation sets account for 74% of our one-line usage examples. I intend to do more work directly with the teams that maintain these two documentation sets to establish standards around when and how to include one-line usage examples, and when they should be expanded to show more of the surrounding context.

In contrast, only a small percent of the code examples in our documentation counted as “complex” code examples.

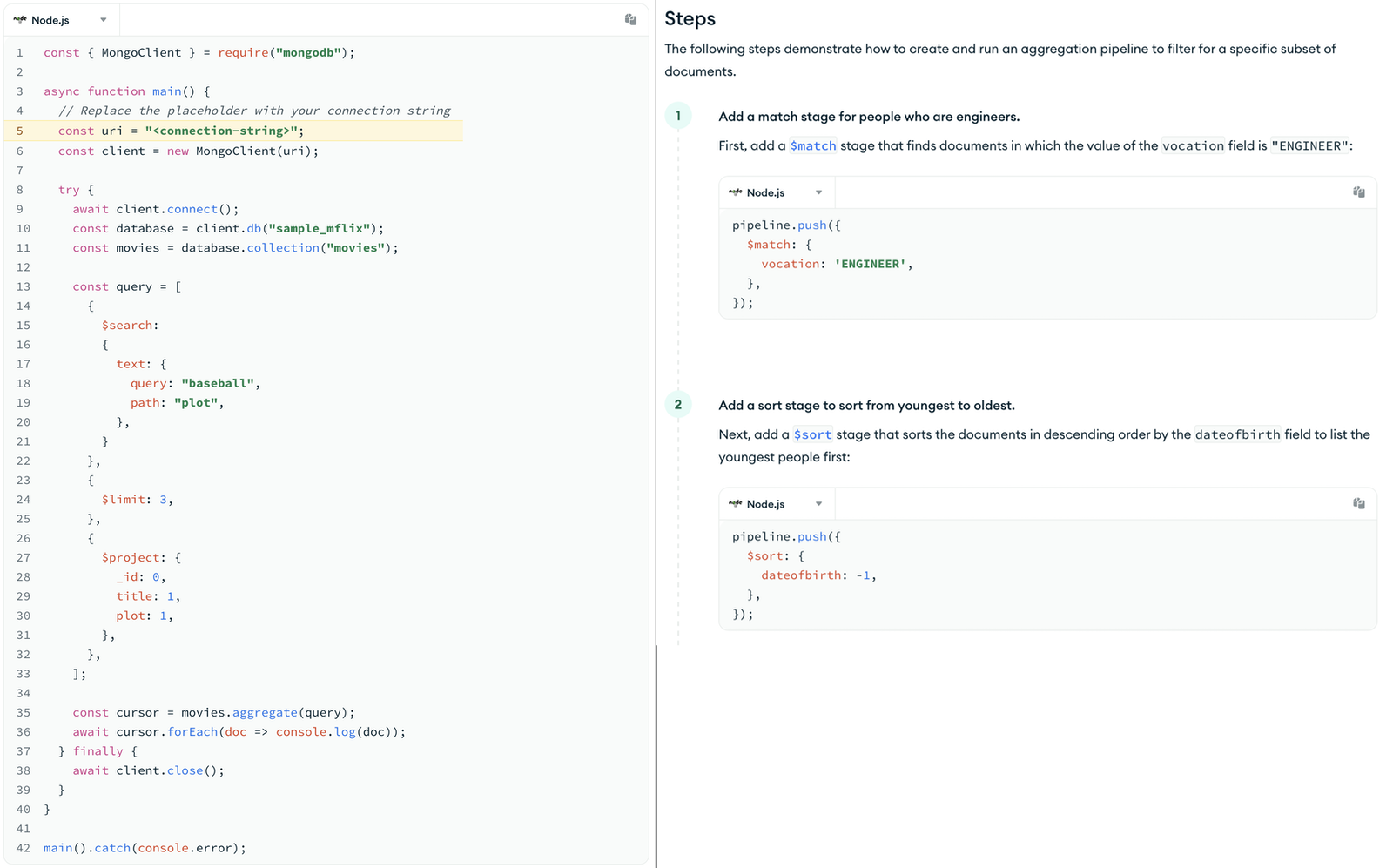

In some cases, this is because some of our docs break down more complete usage examples into bite-size, copyable bits with explanation. Consider these two similar examples:

On the left, we have a larger code block that a developer might copy and modify to use in their own code.

On the right, we have small code blocks broken down step-by-step with text explanations that accompany each step. If all of the steps were combined into one code block, it would be similar in length and complexity to the one on the left.

Developers are unlikely to copy these small code blocks because they would have to copy many of them in a row to build up to a similar example. It would be faster to use the IDE autocomplete to write this code than to copy and paste each individual block from our documentation.

Both of these ultimately illustrate examples of similar real-world usage. But the one on the left fits our criteria for “real-world usage example”, while the ones on the right do not. So the one on the left gets counted, while the ones on the right don’t.

In other cases, we simply don’t show the larger context of a usage example. I believe we have APIs and parameters that are not covered at all by usage examples. Which brings us to the next research question.

Ultimately, the purpose of this audit was to identify gaps in our code block coverage and scope work to close those gaps.

But, with some of the questions above, you can begin to see how the answer is “it’s complicated.”

We now have the data and pipeline to measure our code block coverage.

If we can determine what measurements we need.

What is ultimately missing as we try to answer this question is the business intelligence around what code coverage we need in our documentation.

Ultimately, my conclusion was that after completing the audit, we have a good understanding of the current distribution of our code blocks. However, we need to do more alignment with our partners in Product, Technical Support, and other parts of the organization to create a framework for how much coverage is needed relative to various axes. I suggested we continue the alignment phase with the following action items:

In practice, months after completing the audit, we have aligned with key stakeholders in the organization to prioritize code blocks serving the developer persona for specific product features that demonstrably lack coverage.

I would like to see us continue to build business intelligence around what code example coverage we need so we can measure our coverage with the tooling we’ve built and identify and scope projects based on the intersection of this data.

The audit showed me that we have an untenable number of code examples across our documentation. Given the resources we have, we simply cannot actively maintain all of the existing code examples. I have concluded that any given code example in our documentation must:

This does not reflect the current reality of our documentation. At this time, any given code example in our documentation may fail one or more of these criteria. The surface area is just too large. We are only beginning to implement systematic, repeatable testing to streamline the maintenance of our code example assets. So I wanted to know if there were places we could remove low-value code blocks to remove possible points of failure for developers attempting to use our documentation.

I dermined the following steps could help us identify and eliminate low-value code blocks in our documentation:

If we took these steps, we could eliminate thousands of low-value code examples from our documentation, reducing our mainteance surface area significantly.

While the audit in isolation couldn’t necessarily answer all of our questions without the business intelligence to derive the appropriate measurements, I learned a lot about our code example landscape across our documentation. I’ve made recommendations based on my findings across three key areas:

We’ve already been able to implement some of the recommendations, and are working on planning/prioritizing additional work. In the next article in this series, I’ll wrap things up with a summary of the recommendations I made, why each recommendation is important, and the expected business impact of implementing those recommendations.