Case Study - 'upgrade-stripe' Agent Skill

In which I deep dive on a Stripe Skill, and what it means for the industry.

With over 35,000 code examples, there’s no way our docs organization could afford for people to spend time manually assigning a category to each code example. Humans apply criteria selectively, too, which means we would categorize code examples inconsistently. When we started talking about an audit, I had recently written code examples using Go with a local LLM, Ollama, to perform some embedding generation and summarization tasks. I wondered if we could use Ollama to categorize our code examples, so I spent a few hours writing a proof-of-concept to test the idea. I iterated on the prompt until I got 90% accuracy with my test data, and called that “good enough” to validate the concept. It worked! We could use an AI to assign categories to the code examples.

In practice, it turned out to be - a little more complicated.

The PoC was simple:

During the PoC phase, I tested out the categorization process with a variety of models from OpenAI, the Hugging Face model hub, and Ollama:

I was writing this PoC during a few hours on a Friday, and didn’t want to wait to get organization funding to use a more expensive LLM API, so I didn’t try out OpenAI’s more recent/expensive models. I just threw a few bucks in a personal account and used GPT 3.5 turbo. My colleagues in the Education AI team have suggested that GPT 4o and later may perform better at this task than 3.5 turbo, but I didn’t want to spend the money on the more expensive model for my PoC testing.

I found that Ollama’s qwen2.5-coder model far outperformed the other models in testing accuracy. This model was developed specifically for code generation, code reasoning, and code fixing, and that seems to give it an edge when evaluating code using my definitions. The other models are more general text processing and question-answering models, and don’t seem to perform as well when reasoning about code example text.

When I wrote the PoC, I iterated on the prompt until I landed on this prompt:

// CategorizeSnippet uses the LLM categorize the string passed into the func based on the prompt defined here

func CategorizeSnippet(contents string, llm *ollama.LLM, ctx context.Context) string {

// To tweak the prompt for accuracy, edit this question

const question = `I need to sort code examples into one of four categories. The four category definitions are:

API method signature: One-line or only a few lines of code that shows an API method signature. Code blocks showing 'main()' or other function declarations are not API method signatures - they are task-based usage.

Example return object: Example object, typically represented in JSON, enumerating fields in the return object and their types. Typically includes an '_id' field and represents one or more example documents. Many pieces of JSON that look similar or repetitive in structure probably represent an example return object.

Example configuration object: Example object, typically represented in JSON or YAML, enumerating required/optional parameters and their types.

Task-based usage: Longer code snippet that establishes parameters, performs basic set up code, and includes the larger context to demonstrate how to accomplish a task. If an example shows parameters but does not show initializing parameters, it does not fit this category. JSON blobs do not fit in this category.

Given those categories, which one applies to this code example? Don't list an explanation, only list the category name.`

template := prompts.NewPromptTemplate(

`Use the following pieces of context to answer the question at the end.

Context: {{.contents}}

Question: {{.question}}`,

[]string{"contents", "question"},

)

prompt, err := template.Format(map[string]any{

"contents": contents,

"question": question,

})

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to create a prompt from the template: %q\n, %q\n, %q\n, %q\n", template, contents, question, err)

}

completion, err := llms.GenerateFromSinglePrompt(ctx, llm, prompt)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to generate a response from the given prompt: %q", prompt)

}

return completion

}

I grabbed live code examples from our documentation that matched the category definitions, added simple tests to validate the LLM assigned the correct category for each example, and tested the prompt.

I got 90% accuracy with my test data with this prompt. My test results showed the LLM correctly categorizing the prompt most of the time. It occasionally got confused about example return objects. I figured we could iterate on the prompt until we could get the LLM to categorize return objects correctly.

If you’ve been reading the other articles in this series, you may notice the categories in my prompt here don’t match what I described in Audit - What is a code example? I wrote this PoC before we had aligned about categories across the docs organization. When I actually started running this tooling to perform the audit, I iterated on categories to match our definitions - and then more as I validated the results.

After validating that this should work in theory, we leveraged my PoC when the time came to perform the audit. I updated the prompt to match our agreed-upon category definitions, and started running it across real-world data sets - our various documentation projects.

It became obvious quickly that time and accuracy considerations required some refinement on my PoC.

I quicky discovered that it would take a long time to have the LLM running on my machine categorize all of these code examples. I decided to run each project manually, one-by-one, so I could evaluate accuracy while subsequent projects were running.

As an aside, I also discovered that my 4-year-old personal laptop with maxed out hardware ran the job 3-4x faster than my 2-year-old work laptop. Since I wasn’t doing anything proprietary - I was running an LLM over our public-facing documentation, which I was getting from an API endpoint that did not require any sort of authentication - I decided to run the tool from my personal laptop and then transfer the reports to my work laptop for validation. Hooray for maxed-out hardware. It took about 26 hours to run the tooling over our entire corpus from my personal laptop.

A teammate helped me use a manual quality assurance process to validate the LLM categorization results. We picked examples semi-randomly across a given documentation project, looked at the code example text, and assessed whether we agreed with the LLM’s categorization. We recorded the results in a spreadsheet, giving the LLM a “pass” or “fail” to indicate whether the category was accurate. We tried to select a representative sample of examples for validation in different topic areas and with different category types. Our findings revealed a problem:

Accuracy plunged from 90% to 36.7% when categorizing a real-world data set.

My tiny selection of happy-path code examples was not at all representative of the results of running this tooling across a real-world data set.

Some code examples seemed to cause the LLM to hallucinate. The LLM was supposed to return only category names. In practice, it sometimes returned random text instead of one of my supplied category names. I initially thought this might occur in long-running jobs where the LLM got confused, but I eventually found some short jobs where it returned random text.

I added logic to check if the returned text was one of my category names, and if not, have the LLM try again to categorize the example. It got stuck in an endless loop. I tweaked the logic to retry a fixed number of times, and then just give up and return “undefined.”

In cases where it returned random text on the first try, the result never seemed to change no matter how many times I re-ran the specific example. It always returned the same random text for a given example, which may differ from the random text it returned for a different example. I theorize that something in the code example text may be improperly escaping my prompt and causing the LLM to return something other than what the prompt instructs.

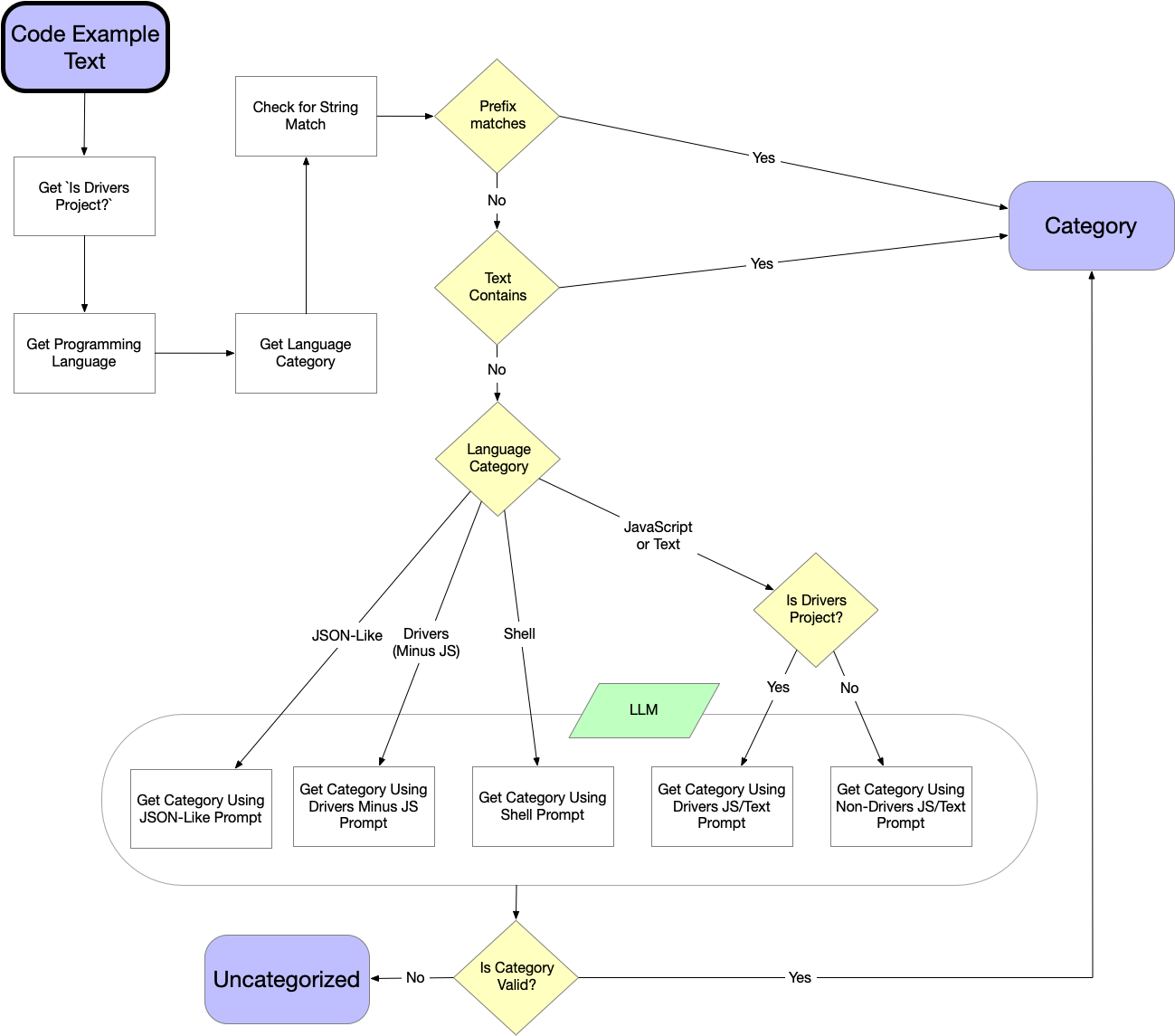

As we validated the LLM’s categorization, patterns emerged. I realized we could synthesize rules based on these patterns to improve accuracy. This quicky turned into a hybrid categorization process:

The simple pipeline in my PoC above turned into this:

To improve time-based performance, I apply rules from the fastest to the slowest process. Prefix matching is the fastest, followed by text substring matching, and then using the LLM. String matching takes on the order of less than a second, while LLM-based matching takes anywhere from 7-15 seconds depending on the code example. When running across 35,000+ code examples, that difference adds up.

As I looked at code examples where categorization failed, I saw some of the same things over and over again. I realized we could generalize to say that if a specific string matching rule applied, the code example belonged in a given category. As I looked at more code examples, I applied string-matching rules conditionally - if the code example language category was this type, I applied the string matching rules, but not if it was that type.

The string matching rules are generalizations that may not apply in every scenario. I’m calling them 99% accurate based on my QA of the string matching results. In practice, this number may be lower, but two people could only evaluate so many code examples within our iteration period.

Some code examples always start with a specific series of characters. And those strings are most predictable when the code examples aren’t for or about our product. I discovered through this audit that a lot of our code examples are actually instructions for using third-party tools - package managers, file systems, etc. So I developed a new category: Non-MongoDB Commands.

As we checked our code examples for accuracy, I spotted these prefix matches over and over again, so added specific handling for them:

// These prefixes relate to syntax examples

atlasCli := "atlas "

mongosh := "mongosh "

// These prefixes relate to usage examples

importPrefix := "import "

fromPrefix := "from "

namespacePrefix := "namespace "

packagePrefix := "package "

usingPrefix := "using "

mongoConnectionStringPrefix := "mongodb://"

alternoConnectionStringPrefix := "mongodb+srv://"

// These prefixes relate to command-line commands that *aren't* MongoDB specific, such as other tools, package managers, etc.

mkdir := "mkdir "

cd := "cd "

docker := "docker "

dockerCompose := "docker-compose "

brew := "brew "

yum := "yum "

apt := "apt-"

npm := "npm "

pip := "pip "

goRun := "go run "

node := "node "

dotnet := "dotnet "

export := "export "

sudo := "sudo "

copyPrefix := "cp "

tar := "tar "

jq := "jq "

vi := "vi "

cmake := "cmake "

syft := "syft "

choco := "choco "

I check the code example text against each of these prefixes. If the language is in a specific language category, and the prefix is in one of these prefix buckets, I return the relevant category - i.e. Syntax example, Usage example, or Non-MongoDB command.

Prefix checking is the fastest of the rules to apply, so I start by checking the prefixes, as this only requires us to parse the first N characters of the code example text for each of these prefixes.

Sometimes, a code example contains a specific string, but it may not be right at the beginning of the example. So for this smaller selection of strings, I check if the code example text contains this string in the first N characters - 50 currently, but we could expand it to a higher number to catch more cases at the cost of slower processing.

// These strings are typically included in usage examples

aggregationExample := ".aggregate"

mongoConnectionStringPrefix := "mongodb://"

alternoConnectionStringPrefix := "mongodb+srv://"

// These strings are typically included in return objects

warningString := "warning"

deprecatedString := "deprecated"

idString := "_id"

// These strings are typically included in non-MongoDB commands

cmake := "cmake "

If none of the prefix matches apply, I check the first N characters of the code example text for each of these substrings. If the code example contains one of these substrings, I return the appropriate category.

LLM categorization accuracy improved when I used fewer category names in the prompt, and gave it more detailed definitions. So I created multiple, more restricted prompts. I grouped the programming languages into categories, and used the programming language category, plus whether or not the project was a Drivers project, to select one of three prompts when using the LLM to assign a category.

JSON and YAML are almost always one of two categories:

I could probably get even more granular and say that if a code example is YAML, it’s always a configuration object example, and use this prompt only for JSON.

const questionTemplate = `I need to sort code examples into one of these categories:

%s

%s

Use these definitions for each category to help categorize the code example:

%s: An example object, typically represented in JSON, enumerating fields in a return object and their types. Typically includes an '_id' field and represents one or more example documents. Many pieces of JSON that look similar or repetitive in structure.

%s: Example configuration object, typically represented in JSON or YAML, enumerating required/optional parameters and their types. If it shows an '_id' field, it is a return object, not a configuration object.

Using these definitions, which category applies to this code example? Don't list an explanation, only list the category name.`

question := fmt.Sprintf(questionTemplate,

ExampleReturnObject,

ExampleConfigurationObject,

ExampleReturnObject,

ExampleConfigurationObject,

)

MongoDB provides language-specific Drivers to work with the DB more easily and idiomatically in a given programming language. If the project is a Drivers documentation project, and the programming language is one of the Drivers programming languages, the example is almost always one of two categories:

For example, if I’m in a Drivers project, and the code example programming language is Python, it’s probably not a configuration object or a return example. It may be a Non-MongoDB Example, but the LLM doesn’t have enough knowledge about MongoDB APIs to apply that category with accuracy. So if we don’t catch it with the string matching rules, we assume it’s one of these category types when we ask the LLM to categorize it.

const questionTemplate = `I need to sort code examples into one of these categories:

%s

%s

Use these definitions for each category to help categorize the code example:

%s: One-line or only a few lines of code that shows the syntax of a command or a method call, but not the initialization of arguments or parameters passed into a command or method call. It demonstrates syntax but is not usable code on its own.

%s: Longer code snippet that establishes parameters, performs basic set up code, and includes the larger context to demonstrate how to accomplish a task. If an example shows parameters but does not show initializing parameters, it is a syntax example, not a usage example.

Using these definitions, which category applies to this code example? Don't list an explanation, only list the category name.`

question := fmt.Sprintf(questionTemplate,

SyntaxExample,

UsageExample,

SyntaxExample,

UsageExample,

)

There is a caveat around this: a lot of code examples across our documentation are labeled as JavaScript. This label is technically correct from a syntax highlighting perspective, but probably doesn’t actually represent what a developer wants when they search for a “MongoDB JavaScript example.” I’ll get into this more in the Audit Recommendations article (coming soon). But for the purpose of using the right LLM prompt, I can’t make this generalization about JavaScript even if I’m in a Drivers project.

When the programming language label on a code example is JavaScript, Text, or Shell, it could be any of our categories. I’ll get into this more in the Audit Recommendations article (coming soon), but for the purpose of using the right LLM prompt, I have to pass these examples to the most “open” prompt that includes all of the possible categories.

const questionTemplate = `I need to sort code examples into one of these categories:

%s

%s

%s

%s

%s

Use these definitions for each category to help categorize the code example:

%s: One line or only a few lines of code that demonstrate popular command-line commands, such as 'docker ', 'go run', 'jq ', 'vi ', 'mkdir ', 'npm ', 'cd ' or other common command-line command invocations. If it starts with 'atlas ' it does not belong in this category - it is an Atlas CLI Command. If it starts with 'mongosh ' it does not belong in this category - it is a 'mongosh command'.

%s: One-line or only a few lines of code that shows the syntax of a command or a method call, but not the initialization of arguments or parameters passed into a command or method call. It demonstrates syntax but is not usable code on its own.

%s: Two variants: one is an example object, typically represented in JSON, enumerating fields in the return object and their types. Typically includes an '_id' field and represents one or more example documents. Many pieces of JSON that look similar or repetitive in structure. The second variant looks like text that has been logged to console, such as an error message or status information. May resemble "Backup completed." "Restore completed." or other short status messages.

%s: Example object, typically represented in JSON or YAML, enumerating required/optional parameters and their types. If it shows an '_id' field, it is a return object, not a configuration object.

%s: Longer code snippet that establishes parameters, performs basic set up code, and includes the larger context to demonstrate how to accomplish a task. If an example shows parameters but does not show initializing parameters, it is a syntax example, not a usage example.

Using these definitions, which category applies to this code example? Don't list an explanation, only list the category name.`

question := fmt.Sprintf(questionTemplate,

NonMongoCommand,

SyntaxExample,

ExampleReturnObject,

ExampleConfigurationObject,

UsageExample,

NonMongoCommand,

SyntaxExample,

ExampleReturnObject,

ExampleConfigurationObject,

UsageExample,

)

Because this prompt is so open, and the text in the code examples may not exactly match what is described here, the LLM struggles to apply it accurately. Anything that uses this prompt is the least likely to be accurate.

This iteration process dramatically improved accuracy - the string-matched code examples were accurate 99% of the time. So if I could track whether a code example was LLM-categorized, I could estimate a rough accuracy for the entire collection.

I added an llm_categorized bool to the code example metadata to track how a given code example was categorized. I could figure out how many code examples were string matched and LLM-matched relative to the total code example count, and estimate accuracy for each of these categories, to get a total accuracy estimate across the collection.

// Calculate the percentage contribution of stringMatchedCount and llmCategorizedCount

stringMatchedPercentage := (float64(stringMatchedCount) / float64(totalCodeCount)) * 100

llmCategorizedPercentage := (float64(llmCategorizedCount) / float64(totalCodeCount)) * 100

// Calculate accuracy estimate for each categorization process

stringMatchAccuracy := float64(stringMatchedCount) * 0.99 // 99% accuracy

llmCategorizedAccuracy := float64(llmCategorizedCount) * 0.6 // 60% accuracy

// Combined accuracy calculation

return (stringMatchAccuracy + llmCategorizedAccuracy) / float64(totalCodeCount) * 100

This was only a rough guideline, but it gave us a snapshot of how much we could rely on the results when looking at a given documentation set.

By the time we completed the audit, the Drivers docs sets, which have a much more uniform and restricted code example structure, were back up to estimated 90% accuracy. Our larger documentation sets, with much less uniform code example structures and prompts that use the more open category definitions, are estimated at a much lower 40% accuracy.

I would love to spend more time iterating to improve accuracy across our documentation sets. I believe, given time, I could continue to refine string-matching rules and LLM prompts to improve accuracy to a uniform 80% or higher. But we have reached the point of diminishing returns. I’ve covered the “easy” accuracy gains, and anything I do from here will be a much more manual and time-consuming iteration process. Unless the organization decides that it wants to invest more heavily in improving this accuracy, I don’t feel justified spending more time on this task.

If I did get the opportunity to spend more time on this, I’d work across multiple axes to improve our accuracy:

The string-matching rules I identified here were from a couple of days of manually verifying audit results. If I had time to look at more code examples across more documentation sets, I could synthesize more rules and define more conditions to apply the rules. This would enable me to boost accuracy by increasing the number of examples categorized using the more accurate and performant string matching.

I started with one prompt, and ended with three prompts. I think I could develop additional prompts, or customize the category definitions for a given prompt, to enable the LLM to perform more accurately in a given documentation set. This would enable me to boost the LLM’s accuracy when I do ask it to assign a category.

Right now, a code example labeled with the programming languages JavaScript, Text, or Shell could be virtually anything. In some cases, we correctly apply these programming languages for syntax highlighting purposes but they don’t actually represent what a developer wants when they search for a given language. In other cases, we apply these labels incorrectly - calling something “Shell” when we output it in the console, instead of the more accurate “Text” label since output is almost always a simple text message. By conflating syntax highlighting and development environment with programming language, we compromise the quality of our data. If I could improve the quality of our programming language labels, our categorization efforts would be more accurate.

I’d love to try something meta and ask an LLM to create string-matching rules or define category definitions to use in an LLM prompt for a given set of code example inputs. At the core, an LLM is a really complicated pattern-matching machine. I’d love to see if I could harness this to have it synthesize rules or prompt text to improve the accuracy of the categorization process.

I’d love to spend some time, and maybe even enlist some of my other teammates, to manually verify high-priority product areas or documentation pages where the LLM has categorized code examples. I’d like to add a verified bool to anything we manually verify, and have us input the correct code example category in the database. This would enable us to improve our accuracy estimate - i.e. anything that is llm_categorized and has a verified value of true is 100% accurate.

Now that we have the code example category, we can model our code example metadata and insert it into a database. I’ll go more into the data modeling decisions we made, and what they enable, in the Modeling Code Example Data article. Category became a key reporting metric in our Audit Conclusions, and factored heavily in the Ongoing Code Example Reporting considerations (coming soon).