Inside the Code Example Comparison APIs

In which I deep dive into the problem domain to discuss the problems we had to solve.

Having defined categories to better quantify our code examples, and identified the data we wanted to track, we were ready to start the audit - right? One more technical design decision awaited us - how should we access the content we wanted to audit? Our directive was to “count the code examples in our documentation” with the ability to “break down counts by programming language.” Our documentation content source spans more than 50 git repositories, across tens of thousands of files, and with many different git branching schemes. So, how were we going to source the content we wanted to audit? And how were we going to access the data once we knew what content we wanted to audit?

In the last article, I mentioned that as part of deciding what information to track:

My lead polled leads across the documentation org to figure out which documentation sets we wanted to evaluate. We ended up with a list of 39 documentation sets to evaluate, omitting low-priority, deprecated, or no-longer-actively-maintained documentation sets.

This narrowed the scope of “our documentation” to 39 documentation sets. But there’s another nuance to this question - what git branch should we audit in each repository?

We version some of our documentation sets to match the product version. For example, our “Manual” matches the MongoDB Server version, and our Drivers documentation sets each match their relative Driver versions. But we don’t expose some of our product versions publicly, so we don’t maintain versioning for all of our documentation sets. We also have documentation repositories which, in some instances, go all the way back to 2007. We have used different branch naming schemes over the years. So even our non-versioned docs sets don’t have a consistent branch naming scheme for the main branch.

Practically speaking, if we wanted to audit only the “current” version of the documentation in each documentation set, we had to figure out what git branch we needed to care about in those 39 repositories.

Our org maintains a separate system to track that mapping. We don’t expose it as metadata anywhere in the git repository directly. So if we wanted to audit the “current” content in each documentation set, the process would look something like this:

This is definitely something we could do programmatically. But the more systems we interface with, the more permissions we need and the more potential there is for something to go wrong.

Beyond the question of git branches and permissions, we had another question to answer - how do we get the information we need from the relevant docs content?

As I mentioned in the last article, our organization authors documentation content in the markup language reStructuredText (rST). rST, being a product of the Python community, is a whitespace-sensitive markup language that presents some interesting challenges when you want to parse and extract specific elements of the content.

The source for a code example might look like this:

.. code-block:: java

// Run this on the device to find the path on the emulator

Realm realm = Realm.getDefaultInstance();

Log.i("Realm", realm.getPath());

When rendered to an abstract syntax tree (AST) representation of the content, this is what the code example looks like:

{

"type": "code",

"position": {

"start": {

"line": 6

}

},

"lang": "java",

"copyable": true,

"emphasize_lines": [],

"value": "// Run this on the device to find the path on the emulator\nRealm realm = Realm.getDefaultInstance();\nLog.i(\"Realm\", realm.getPath());",

"linenos": false

}

If you’ve ever worked with JSON, you know it’s pretty trivial to:

"type": "code""lang" value ("java")"value" value, which is the code block itselfBut if you instead had the raw page text, you’d have to:

.. code-block:: instances.. code-block:: directive and becomes something elseWithout a closing tag, you’re relying on a change in indentation to know you’ve reached the end of the directive value.

And then you’d have to do it all again for each of the directive types that can represent code examples in our documentation. We have four of them.

Again, all of that is do-able, but requires a lot more code to properly extract the bits we care about than just pulling some values from specific fields of an AST representation of the content.

The best (read: least hacky and error-prone) option would probably be to use the actual reStructuredText tooling to construct an AST from the source files, and then get what we need from the AST. But we’ve got one minor issue with that - our documentation uses a lot of custom rST directives and roles. If we don’t register those directives and roles with the parser, the parser throws an error when it gets to something it doesn’t know how to process. We could maybe modify it to throw out an error when it’s a directive type we don’t care about, and only register the code-related directives we do care about. But that’s also getting into the realm of more code than we’d like to write and maintain, and is literally error prone because we’re trying to discard some but not all errors.

Some of you are probably thinking “Wait a minute! If you’ve already got a system that knows how to parse this content properly, with all the right directive and role information, why don’t you just use your existing build system to process the files and turn it into AST you can operate on?”

You’re not wrong! That’s an option. Our parser is in a public repo that anyone can view right here: snooty-parser. I started digging into this for this purpose, and discovered pretty quickly that there’s a lot going on here. Over many years, we have taken bits we want from docutils, the official system written to process rST, and we use those in concert with another system that we forked somewhere along the way, and other bits of our own home-grown tooling, and somewhere in the intersection of all this is the code we need to turn rST into an AST we can work with easily.

If I gave myself more than a couple of hours to spelunk in this, I’m sure I could eventually read enough of the code to figure out what’s going on and which parts we actually need to do what we want to do. But it would be a non-trivial time commitment for a one-time audit to help us get a better picture of the code examples we have across our documentation.

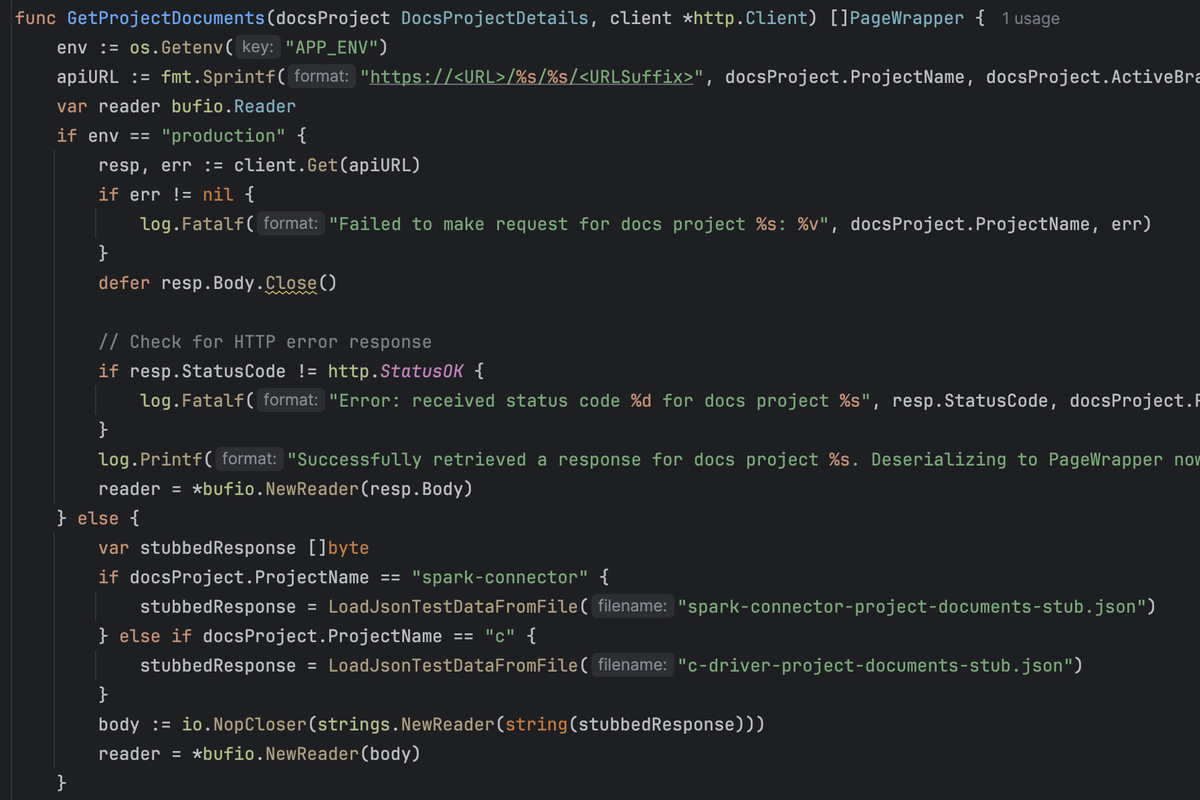

Accessing the data we care about is a more complicated problem than it might seem at first glance. Fortunately, we’re not the first people in our organization who have wanted to operate programmatically across our documentation sets. My former lead, who is now our Director of Engineering for our documenation platform (and various other education platforms), wrote a tool a few years ago to programmatically operate on our rST. My current lead made a first pass at extending some of the existing functionality to perform the audit.

This tool was able to shortcut a lot of the really complicated issues. The director had already written code to:

This API response provides newline-delimited JSON blobs containing the AST of all of the pages and assets in the documentation project for a given branch. It’s already in AST, so it’s relatively simple for us to extract the keys and values we care about. It’s a lot easier to make a couple of API calls to get the “current” live version of our docs pages than to manage git branches and traverse files on the local file system.

Working with this API, and basing our tooling on something that already existed, gave us a big head start on producing tooling fast to complete the audit.

There’s one wrinkle: the API is an undocumented internal API that I had never heard of before. It’s maintained and used by another team for its own purposes, and there is no guarantee of stability or availability. This wasn’t a problem during the initial audit. As we spotted issues with our tooling and tried to re-run reports, though, we did have to work around some changes and some times when the data wasn’t available from the API.

This tool to operate on our docs is a TypeScript tool. I’m not a TypeScript dev. I can fumble my way through it, but I’m sure the code I write isn’t idiomatic. And it’s not the first tool I reach for when I’m working on my own code.

When I hacked together a proof-of-concept of using a local LLM to categorize the code examples, I wrote the project in Go. I had just been working on some Go LLM code examples for our documentation. It was fresh in my mind, I already knew what dependencies and APIs I needed, and I was able to put something together pretty quickly. It was something I threw together just to see if it would work, and this was before we had started to think about how we might operate programmatically across many docs sets.

The first pass that my lead made on the TypeScript tool to operate on our docs was already writing the results to JSON “reports” on the file system when he handed it off to me. It was trivial for me to extend the code he had already written to write the code examples I needed to categorize to files on the file system. Then, my Go tooling could ingest those code example files, categorize them, and write its own JSON with the results.

From there, I wrote another small tool to ingest the JSON output from both the other tools and create a consolidated report. This one was in TypeScript, with the thought that maybe someday we could munge everything together into a TypeScript tool if we wanted to repeat the process.

Meanwhile, as I was starting to complete the audit, my lead started asking about different ways to slice the data. I modified my JSON reporting tool to slice the data in different ways, but it was pretty obvious that we actually wanted to do this dynamically. One of my teammates wrapped up a project, and jumped on writing a tool to ingest our JSON data into a database. He wrote that tool in Go.

So now we had a very hacky pipeline to perform our audit that looked something like this:

This was obviously not ideal, but this is what we ended up with from the very vague directive “count the code examples in the documentation” and “break down counts by programming language.” In the end, we had a dynamic way to access the audit data - interact with the database to slice the data however we needed it.

Working with data from the API simplifies a lot of complicated implementation details, but we are missing a few things by working with this information versus working with the git repositories on a file system.

By not working directly in the git repositories, we miss out on git metadata that we might otherwise find useful to track. If we were working in the git repository directly, we could use git metadata to find out when a code example was created, when it was last updated, and who worked on it last. If we had created and updated dates, we could find code examples that haven’t been touched since X date and:

If we had data about the last person to work with a code example, we could potentially assign tickets to that person to and/or to route issues to them. The person who worked on the code most recently is probably a good starting point for additional work or changes.

The API does not expose any git metadata beyond the branch used to generate the documentation set. If we wanted git metadata for files or lines in a file, we would need to operate directly on the files in the git repository.

The API provides information in the context of a documentation page. This lets us tie code examples to specific documentation pages, so we can examine the code examples in the context of how a reader interacts with them. However, a documentation page could be built from many different files in the git repository. Our documentation makes heavy use of rST’s transclusion functionality - the ability to pull in the contents of many different files to build a single page.

If we use the audit data to find specific code examples, we get that information back in terms of the pages where the examples appear. However, if a writer needs to perform some maintenance on a code example, they have to work backwards from the page URL to find the file that contains the code example itself. In some cases, this could involve many hops.

If we were parsing the code examples from the files directly, we could store metadata about the file - its name and location, for example. This would enable us to tie a code example directly to the file that contains it, simplifying maintenance tasks.

We track product and sub-product information programmatically through special files located in root directories of the documentation repositories. However, we don’t expose that product information through the API. We can only get that information programmatically by working directly with the file system.

When we got the request to correlate code examples with products and sub-products, it was after we had built the audit tooling using the API. My “quick” proxy was to manually create a mapping between documentation sets and directories and their products and sub-products. Then, I edited the database entries to add this information to every “page” entry.

This works, but relies on my manual mapping. When that product and sub-product information changes - if we add a new sub-product, for example, or change our content structure so sub-product documentation comes from a different directory - my mapping is out of date. We should really be pulling this information programmatically from the files in the repositories to keep it up to date.

We’re relying on an API that another team created and maintains for its own purposes. The API has no versioning and no documentation. While working on the audit, the team that owns the API made various changes that resulted in the API:

In each of these cases, I’ve had to ping the team that owns the API to ask if this is expected or unexpected, and if there is any workaround. I’ve had to write additional code to handle the various cases, and now some of that code is causing new problems as the data changes again. It’s a little bit like coding on quicksand as this is a changeable API with no guarantees.

I don’t blame the team that owns the API. They have their own reasons for creating and maintaining this API, and I’m just trying to use it because it shortcuts a lot of complexity. But if we want to use this API for regular audits in the future, we need to have a conversation with this team to understand the purpose of this API, and what assumptions we can safely make about it. At the very least, maybe we could get looped into development plans for it so we know when it’s going to change, and what changes to expect. But long-term, we may need to work from the file system directly. Or formalize our usage of this API and add versioning so we can safely rely on the data we get from it.

At this point, the initial audit data is in a database that we can use to dynamically query the data in different ways. For the next few articles in this series, I’ll dive deeper into elements of the audit data for organizations who want to do something similar, such as AI-assisted classification and Modeling code example metadata. After getting the audit data into the database, I spent some time analyzing the data in various ways and comparing it with industry data to draw conclusions about our code example distribution. I’ll explore that in the Audit Conclusions article.

And, spoiler alert - now that we have the audit data, we’ve been asked to develop tooling to re-run the audit on a regular basis and report on changes. I’ll explore that in the Ongoing code example reporting article (coming soon).