Inside the Code Example Comparison APIs

In which I deep dive into the problem domain to discuss the problems we had to solve.

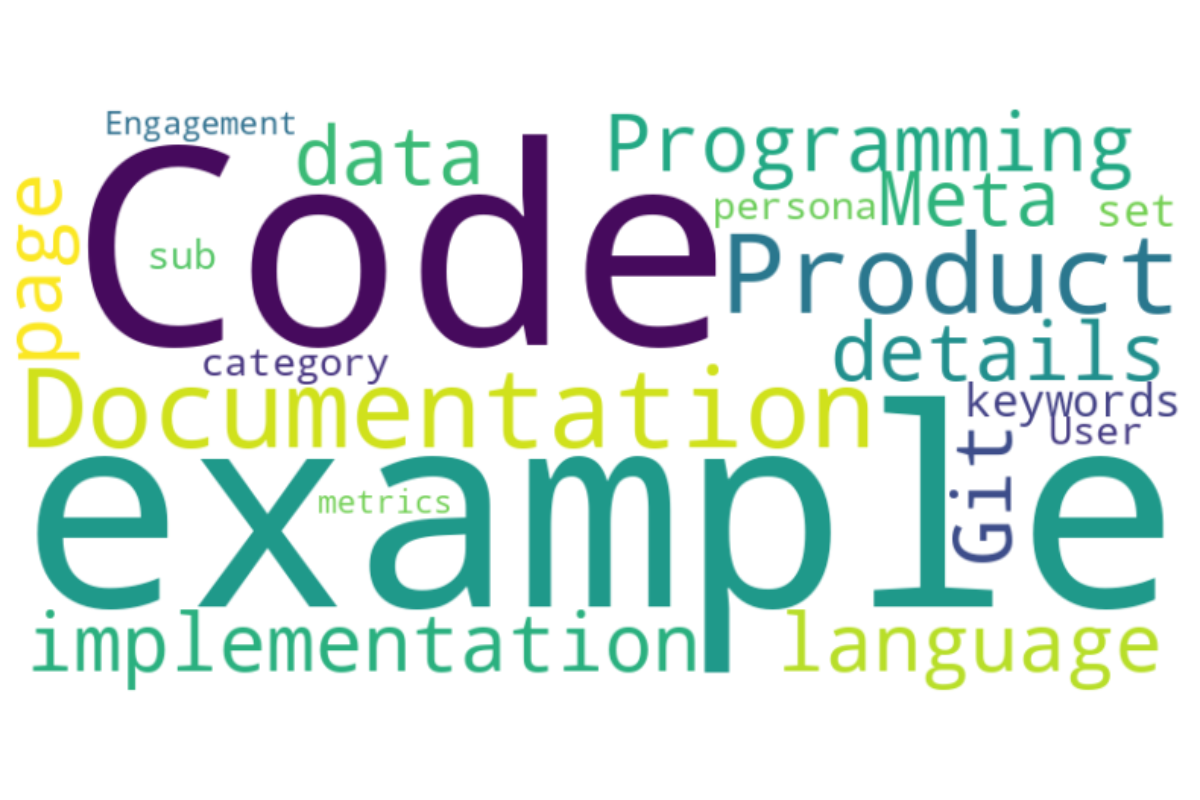

Now that we had defined what we were going to count as a code example, we just needed to count them - right? As I worked on refining the brand-new-tooling we were building out to track this information, I realized we needed a lot more information about what we wanted to track, and how we might want to use the information, to make sure the tooling captured the right details in the right way. As I brainstormed, I wrote a four-page document trying to capture the details; there was a lot to consider. The points break down along these axes:

It became apparent we had to answer a core question before we could figure out the implementation details. What do we want to do with the data?

The initial ask was worded simply: “we want to be able to count the code examples in our documentation.” One person added: “we need to be able to break down the counts by programming language.”

The Education AI team provided those counts last fall, which led to conversations like “we can’t possibly have that many code examples,” and “the distribution across programming languages is surprising.” So we added our code example categories to try to better understand the distribution, and provide a count that was more meaningful for leadership. But the why was still not clearly articulated, and I realized the why would inform a lot of the implementation details.

After digging in, it surfaced that leadership wanted to understand gaps in our code example coverage so we could plan projects to close those gaps and track execution.

I realized that a simple count of code examples broken down by language and category wouldn’t cover this. I also anticipated that my team would have additional uses for information about code examples in our documentation once it was available.

So I needed to dig deeper, and came up with these key questions:

In our current documentation as written, I have access to this data:

Each of these elements gives us something to help us better understand our code example distribution, but some of them require more work to leverage.

My organization authors documentation in reStructuredText (rST). rST provides built-in handling for code, and it also provides tools for extending the markup (directives) when you want to customize handling for specific types of content. In some places, we use the default code handling, but my organization has also defined several custom directives to handle code in our documentation in different ways.

On the most basic, technical level, we can parse the rST in our documentation, find instances of the directives related to code examples, and read their arguments, options, and values. This gives us a list of all of the code examples in our documentation, and any related metadata in the options. At minimum, this gives us:

Depending on the options provided, we may also be able to derive additional information about the code example:

Unfortunately, language is not a required option. The rST parser uses the language option to apply the appropriate syntax highlighting when displaying the code example. When the writer doesn’t provide a language, the rST parser doesn’t apply syntax highlighting.

The use case of wanting to use the language option to programmatically track code examples in our documentation is new. Thousands of examples across our documentation have no language specified, and that is perfectly valid rST. So assumption number one - that we can get a language for every code example - is out the window.

Also unfortunately, web crawlers and LLMs that are parsing our documentation can see the language option in the generated page HTML. This wasn’t really a concern when reStructuredText was first released in 2001, but it is potentially a big issue today. Check out the Audit Recommendations article in this series for details (coming soon).

We could apply a couple of additional techniques to try to derive a programming language when none is provided. When a directive uses a file path to transclude the code example, instead of hard-coding the code example text in the page, we could parse the filepath, look for an extension, and map that to a programming language. For example, a .py file extension is a Python language file; a .cs file extension is C#, and so on. I did implement this to try to improve our counts.

Another other option is to pass the code example text to an LLM and try to get it to identify the programming language. This would add additional time to the processing step, would have taken longer to implement, and the results may not have been accurate enough for our needs. I’m keeping it as an option for future development in audit tooling if we decide we want to prioritize getting a language count for every code example, but at the moment, we haven’t tried doing this.

It’s worth noting that the rST option is “language,” which I mostly use interchangeably with “programming language.” But this option is used for syntax highlighting, which also applies to markup languages and even file formats. YAML and JSON aren’t “programming languages”, but they are valid languages for syntax highlighting. rST front ends often use the Python package Pygments for syntax highlighting, and the Pygments language list is - exhaustive.

For the purpose of this audit, I didn’t take every langauge provided on a code example as written. I defined a list of “canonical” languages based on our docs taxonomy, plus a few additional languages that are not in our taxonomy but seem valid. I ended with a list of 20 lanuages, and did some work to normalize the language option we ingest to one of these 20 languages. Everything that didn’t normalize to a language, or where no language was provided, went into an “undefined” bucket. As we iterate on this process, we can scope work to provide languages where none exist, or update languages to use one of our “canonical” languages.

I also discovered some unexpected consequences of this being an option used for syntax highlighting, which effectively means that a non-trivial number of counts for a couple of languages are effectively bad data. I’ll go into more details about this in the Audit Recommendations article.

We store our reStructuredText documentation files in git repositories. If we wanted to get information like when the code example was added or when it was last updated, it would be possible to do this using git data. However, that has its own complications. It constrains how we can get the data, which I cover in the How can we access the data? article in this series.

More importantly, it requires us to be more sophisticated in how we want to use the code example audit data. An argument could be made that we should regularly revisit code examples after N period of time to make sure they still work. If we could see when a code example was added and last updated, we could generate a list of code examples that should be reviewed to make sure they’re still valid and still reflect best practices. But we don’t currently have a process to do this, a way to assign the work, or the bandwidth to complete it. So parsing the git data to get this information hasn’t become a priority.

I would like to see us get to this point in the future. I’ve added an imperfect proxy for this to the metadata we’re capturing now, which we can leverage in the future if and when we’re ready to invest in this maintenance task.

When we ingest the rST to look for code example-related directives, we examine the rST unit-by-unit. Depending on how we are getting the data we parse, the unit could either represent a file that contains rST or a documentation page.

For reasons I’ll cover in the How can we access the data? article in this series, we’re ingesting units that map to the documentation page. This is data that we can access “for free” as we are retrieving code examples, which we could either discard or record.

Discarding the page data would require the least handling. We could just munge everything into one big counter - or a few big counters, if we want to be able to track programming language and code example category independently. But that would leave a lot of powerful analysis, validation, and future development opportunities untapped.

Because we already have the page data in the context where we’re getting the code examples, it’s a simple bit of additional code to track the page data. And we can do a lot with it. I’ll cover this more in other articles in the series, but I opted to use the documentation page data.

Each documentation page has a set of keywords related to what is on the page. These keywords include information like core functionality, programming language variants, integration frameworks, and other details related to the page.

Since we are already looking at the page data, we have acess to the keywords related to a given page. If we store the keywords related to a given page, we can then correlate code examples on that page with given keywords. We could use this to, for example, find all the code examples related to .NET, or code examples related to aggregation. This gives us a powerful retrieval tool to further analyze our count data.

Our documentation spans many git repositories. This is a legacy of being a large organization with a relatively holisitic documentation process that has evolved over time. Some documentation sets are broken out by product or sub-product. In some cases, we have changed how we think about products and product features as the company evolved, but the documentation is still broken out separately because it started as products. And we have also used separate git repositories to handle documentation that must be versioned independently.

Different documentation sets are managed by different teams. If we wanted to track code example distribution along the axis of which team is responsible for it, we might find it useful to know which documentation set contains a given code example. We could also use it to compare similar documentation sets for gaps; for example, do we have roughly the same programming language coverage between our Node.js and Rust Drivers?

We opted to capture the documentation set in our code example audit data to expand our future analysis options. My lead polled leads across the documentation org to figure out which documentation sets we wanted to evaluate. We ended up with a list of 39 documentation sets to evaluate, omitting low-priority, deprecated, or no-longer-actively-maintained documentation sets.

We knew we wanted to break our code examples down into categories, and that information isn’t currently available in our documentation today. Since we’re already adding data that doesn’t exist today, we looked at other data we might want to use to examine our code examples, and how we might add it. We came up with this list:

We have identified the categories we want to use to drill deeper into our code examples, but we don’t yet have a way to add that information to the code examples. Because we author documentation in rST, we can extend our code-example-related directives to add an option for category, and populate it when we create the code examples. That’s future work we’re planning to do.

In the meantime, we need to assign a category to all of our code examples for this audit. Given the volume - tens of thousands - there is no feasible way we can do that manually. Fortunately, this is an area where AI can help.

In the AI-assisted classification article in this series, I’ll go into more detail about how we used AI to programmatically assign categories to all of the code examples in our documentation. And I’ll detail the iteration and refinement process we used to improve the accuracy of this process. It’s imperfect, but it makes it possible to do something we wouldn’t be able to do at all.

For this audit, we used AI to assign categories to the code examples as we parsed them, and store those categories as metadata on the code example in the database where we’re storing our counts.

As part of the initial information gathering exercise, I asked if we wanted to be able to track the data by product and sub-product. Product does not directly map to documentation set in a 1:1 map, but it is something we can map though metadata.

Unfortunately, the way we have chosen to ingest the data does not expose the product/sub-product metadata that exists in our documentation. If we actually wanted to track product and sub-product, we would need to build additional functionality into the tooling. I raised the question with my lead, who confirmed this would be a “nice to have” but we hadn’t directly had a request to track the data in this way. So we decided to omit building this functionality into the initial version of the tooling.

Amusingly, the following week, we were asked to provide that information. I was still iterating on tooling at that point, so I added functionality to manually insert this metadata. Our information architect had already identified an official list of products and sub-products to use in our documentation metadata. I repurposed this list, created a manual mapping based on docs set and/or subdirectory within a docs set, and added the metadata on the page level. Each page maps to a product, and each code example maps to a page, so we can get a count of code examples by product.

As part of our discussion around what is a code example, we realized we haven’t made a distinction between code examples that serve different personas. Several distinct personas use our products but have differing needs. For the purpose of code examples, we can broadly group personas into two categories:

In some cases, we can broadly group a documentation set with a persona. For example, our CLI for programmatically configuring cloud storage pretty easily maps to a programmatic configuruation persona. But our biggest documentation set has information about both programmatic configuration and for developers who are building apps.

As a proxy for persona, one way we can break down this data is using programming language. It’s not a perfect mapping, but things like YAML and JSON are often used for programmatic configuration, while code in programming languages like Java and JavaScript more likely represents using Drivers to build things with our product. So we can get a rough distribution of code example by persona when we examine documentation set and language.

The holy grail of examining our code examples would be to identify some engagement metrics and use those to see which examples are performing well and which ones aren’t that useful. An obvious proxy for this is how often developers use the “copy” option to copy the code examples in our documentation.

I have theories about why this isn’t actually a useful metric. For things like API method signatures, that information is useful to developers, but developers are unlikely to copy them. Once a developer knows what method signature to use, they can just start typing its name in their IDE and have the IDE autocomplete it, and maybe even populate the relevant arguments. Nobody is going to copy a one-line code example from docs and paste it into their IDE when typing in the IDE provides a much better experience. But having that information in the documentation does let the developer know what method name to start typing.

For longer examples that include setup code, error handling, and actually working with the return object - developers may be likely to copy and paste those examples. If the context is useful and generic enough, developers can just copy it and modify argument names or add logic based on their application needs. Copy data may be a relevant measure of engagement for those examples, but I still think plenty of developers would find these examples useful but not use them directly.

I can think of some other ways to measure engagement, and have made some recommendations around this in the audit report document. I’ll go into more detail in the Audit Recommendations article. But for the purpose of this audit, we don’t yet have a good way to measure engagement, so this is not information that is available to us at this time.

Looking at the information we can get programmatically from our documentation, we have:

I can add some proxy for these additional pieces of metadata:

I can use data analysis and some educated guesses to assess coverage by user persona.

But the objective of this exercise is to:

So now I needed to figure out how I could use this data for this purpose - and what other information might I need.

From this list, we can get a decently granular view of what we have. We can create tooling to re-run the audit on a regular basis, and track changes over time.

What we don’t have in a convenient programmatic form is data about what we need. If we had that data, we could evaluate what we have against what we need to find the gaps.

I’ve been noodling with a framework to try to gather details about what we need. I’ll share that after this audit series.

For the moment, the plan is to take our audit data to key stakeholders across the org, and let the people most familiar with the products use the data to identify gaps. We will serve as a discovery and reporting arm, and align with product experts for gap assessment.

With decisions made about what to actually track, we needed to consider the implementation of how we were going to get, store, and use this information. I’ll cover those details in How can we access the data?.