Case Study - 'upgrade-stripe' Agent Skill

In which I deep dive on a Stripe Skill, and what it means for the industry.

When the Education AI team provided an initial count of code examples across our documentation corpus, broken down by programming language, the numbers were much higher than some members of the org expected. We apparently had tens of thousands of code examples, and nearly 9,000 of those were JavaScript. That couldn’t possibly be right, could it? And more importantly, because the number was so high, how could we break it down to be more meaningful?

This led to a discovery process across the department whose crux was this: what is a code example, really? What should we actually count for the purpose of providing a count of code examples to leadership, and to use to plan future work?

After much iterating, which is detailed in the rest of this article, we came up with these two pieces of guidance to identify code examples in our documentation:

A code example is any block of code that is set apart from the surrounding copy in our documentation.

Code blocks are distinct from monospace “inline code,” which we treat more as page copy than code.

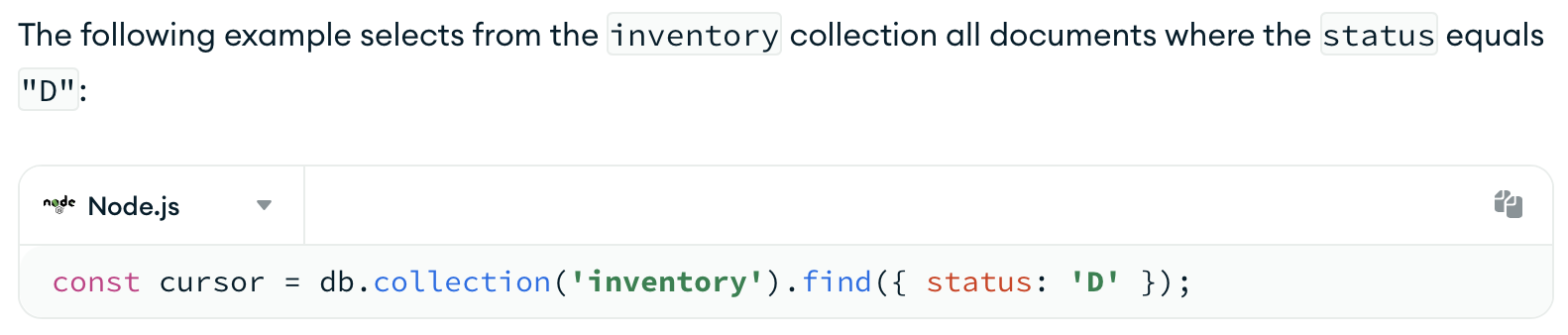

In the following screenshot, the page copy contains the words inventory, status, and "D" in monospace. This is “inline code,” which gives a way to draw emphasis to specific elements of the page copy that are related to code but don’t actually represent code examples themselves.

Below the page copy, there is a display element with a programming language selector drop-down menu where Node.js is currently selected, and a line of code is displayed with syntax highlighting below the drop-down. There is a copy icon in the upper-right corner of the display element. This is a code example.

The distinct display implementation tells developers to pay attention to this content differently than the page copy that surrounds it. The syntax highlighting signals important keywords for the programming language; in this case, type and method calls. And the “copy” icon indicates that a developer may actually want to take some action with this content - i.e. copy it and paste it into their IDE.

With this general definition for code examples, everything that was included in the original counts provided by the Education AI team would actually count as a code example. But we needed some way to get a better understanding of the code examples in our documentation than just “we have tens of thousands, and they’re all the same.” They’re not all the same, but we needed a meaningful breakdown to distinguish them. We had a few false starts, but eventually agreed on a way to count them more granularly.

Some members of the organization initially wanted to count code examples by length, omitting the short “one-liner” code examples. After poking around in the documentation, it became apparent that some of the one-liners definitely have value.

For example, this one-line code example demonstrates the syntax of one of our CLI commands:

atlas clusters indexes create [indexName] [options]

Is it a code example? Should we omit it from the count just because it’s one line? We have thousands of similar examples demonstrating CLI command syntax.

CLI aside, we also have one-line examples that show developers how to use certain specialized syntaxes, or what to expect with certain data types. Is this a code example? Is this not a code example just because it’s one line?

{"created_at": ISODate("2019-01-01T00:00:00.00")}

We also have many examples across our documentation that demonstrate the abstract shape of an object. This is a reference for how developers might form a specific query. Is this a code example?

{ <field1>: <value1>, ... }

Ultimately, we posited that even one-line code examples have value; it’s just a different type of value. We decided we should not omit these from the count entirely, but maybe have a way to track these separately from the more complex examples.

“Complex” is a term that some people use to describe code examples that better match developer needs. I personally dislike the term, because most developers strive for simplicity in their code; it makes code more readable and maintainable. So I don’t think developers actually want more “complex” code examples - they want code examples that more closely resemble real-world usage. Code where you show initializing parameters of specific types, calling one or more methods to do something with those parameters, and then do something with the result - either handle an error, or go on to work with the return object.

For example, we have a very atomic snippet that shows calling a specific method, and assigning it to a variable:

const cursor = db.collection('inventory').find({ status: 'D' });

Or a more “complex” example that shows this code in context:

import { MongoClient } from "mongodb";

// Replace the uri string with your MongoDB deployment's connection string.

const uri = "<connection string uri>";

const client = new MongoClient(uri);

async function run() {

try {

// Get the database and collection on which to run the operation

const database = client.db("sample_mflix");

const movies = database.collection("movies");

// Query for movies that have a runtime less than 15 minutes

const query = { runtime: { $lt: 15 } };

const options = {

// Sort returned documents in ascending order by title (A->Z)

sort: { title: 1 },

// Include only the `title` and `imdb` fields in each returned document

projection: { _id: 0, title: 1, imdb: 1 },

};

// Execute query

const cursor = movies.find(query, options);

// Print a message if no documents were found

if ((await movies.countDocuments(query)) === 0) {

console.log("No documents found!");

}

// Print returned documents

for await (const doc of cursor) {

console.dir(doc);

}

} finally {

await client.close();

}

}

run().catch(console.dir);

These are both examples for the .find() method from different documentation sets; the first one is from our Manual documentation, and the second one is from our Node.js Driver documentation. The second example sets the code in context; it shows the set up you might do before performing the .find() operation and actually doing something with the result.

I believe that both provide value in different ways. Developers who just need a refresh on the syntax - i.e. “what’s the method I use to query multiple documents?” or “how do I form a filter?” - can get what they need from the short reference-style example. But developers who want more comprehensive coverage - for example, a developer who is new to MongoDB, or to using this specific programming language/Driver - could benefit from seeing the more comprehensive example with surrounding context.

With potentially tens of thousands of code examples, the best proxy we could come up to calculate “complexity” in this context is the length of a code example. For the purpose of this audit, we tracked the count of code examples over a specific character length as “complex”.

I was chatting about this after work one day with the wife, who suggested we might want to consider cyclomatic complexity as a truer measure of “complexity.” While that definitely gives a better picture of “complexity” - I think that’s not actually what developers really want from the sample code in documentation. So we stuck with the length as proxy for surrounding context, with the idea that context is really the measure of what developers want.

Even with just the few examples in this article, you can see how there might be a lot of things that could count as code examples. So we needed a way to draw a line in the sand - draw lines in our counts - to help us get a better understanding of what we actually have.

After randomly sampling different pages in our documentation set, I began to observe patterns in what we show in our code examples. It seemed to me that most of the things we show as code examples across our documentation actually provide value to developers, but in different ways. So I wanted to represent these as “types” of code examples.

If we could come up with clear definitions for types, similar to information typing, we could then evaluate what “type” a code example falls into, and count how many we have of each type. We could use these definitions to provide guidance to writers about what should be in a code example for each type, and to evaluate how well code examples match their types. So I started trying to enumerate and define types.

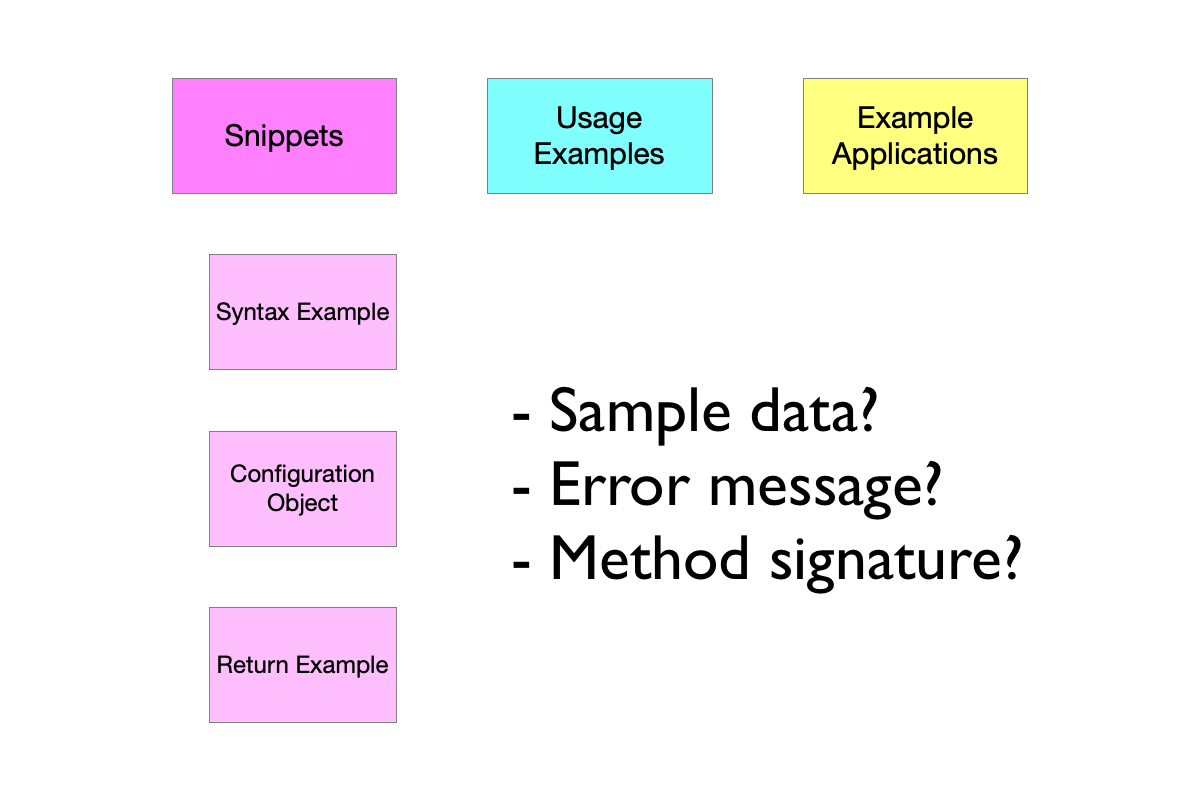

After iterating on various hierarchies, and testing our ideas with different docs leads who regularly work with key stakeholders, it became apparent that the types and definitions we actually need for implementation don’t match what leadership expects to see.

I initially implemented a very granular type hierarchy, but it became apparent that we had “too many” types to easily communicate and report about them to leadership. I simplified the type hierarchy, but then there were a lot of questions about where different examples fit into the hierarchy. It wasn’t obvious enough because the categories were too broad. So we ended up with something in the middle as a compromise - three top-level categories, and then sub-categories for one of the types where it made sense to get more granular. This is the hierarchy we ended up with:

Within the Snippet category, we defined several sub-categories:

When I started actually performing the audit using these code example types, I discovered a large number of code examples that don’t actually document our products - they’re instructing developers to run environment or ecosystem tooling to accomplish a task. This includes things like mkdir, cd, npm install, node filename.js, docker-compose, and other commands that do not actually document our product. I added a category to capture counts of these example types:

mkdir, cd, npm, etc.So the final breakdown of the code example types we used in the initial audit was:

The “snippet” term isn’t actually used as a value in the metadata; a code example is counted as either one of the snippet types, or a usage example. It’s only in the hierarchy for reporting purposes, and to help people understand how we broke down the code examples.

Ultimately, I think this is an imperfect breakdown. When evaluating syntax example versus usage example, we have had difficulty distinguishing these both programmatically and as humans spot-checking the audit results. We have debated whether things like the presence of placeholders affect whether code is a syntax example or a usage example, or whether we can use length as a proxy for determining this. I’ll dig more into this in the AI-assisted classification article.

We also omitted some categories that the Education AI team used in their initial assessment, such as sample data and error message. I would have had a difficult time programmatically assessing whether something was sample data, so I omitted it in this initial round. Error message would have been a subset of return example, and it seemed - unnecessary - to have that level of granularity around that type of return example versus other types of return examples, given the push-back we initially got about the “too granular” hierarchy.

I’d love to iterate on these categories in the future as we continue to build our understanding of what we have versus what developers need. But we also needed to conduct the initial audit, so we deemed this “good enough” to get started.

Unfortunately, our lead is still having challenges communicating with stakeholders about what we actually have in our code examples. Why all the different numbers, and which ones are important to pay attention to?

We’ve been experimenting with different ways to communicate around this, but one distinction I’ve started making is one that I hope sticks: code examples are either informational, or actionable.

I theorize that things like API method signatures are things developers don’t copy from documentation these days; instead, they’ll type whatever they need in their IDE and let autocomplete supply the parameter names and compile-check it. So these examples have informational value - they let developers know what to expect or what pattern or method to use - but developers won’t use them directly.

But multi-line examples that include error handling or other set-up code may be faster to copy and modify. Developers may directly use these code examples. These have actionable value.

Ultimately, this is another arbitrary breakdown which may be imperfect, but it has helped some folks better understand the distinctions we’re drawing.

With these definitions sorted, we had a way to break down our counts more granularly. I thought I had what I needed to perform the audit. But I realized as I started to think about how to build out the tooling to actually complete the audit that these code example types were only one part of the picture. We needed to agree on what we actually wanted to track about the code examples in our documentation.

The next phase in the project would be deciding what to track.