Case Study - 'upgrade-stripe' Agent Skill

In which I deep dive on a Stripe Skill, and what it means for the industry.

I wrote last month about how to test docs code examples. Now, let’s look at what to test in docs code examples.

There are also a couple of “don’ts” when writing and testing docs code examples:

Developer documentation loses trust when the text makes assertions that are not correct. This can happen for a few different reasons:

Fortunately, testing the claims that you make in the documentation gives you a way to catch these errors!

A developer ran into a problem using a map key containing an unsupported character. We added details to the documentation about the disallowed characters for map keys, and suggesting a workaround.

Realm disallows the use of . or $ characters in map keys. You can use percent encoding and decoding to store a map key that contains one of these disallowed characters.

The code example that we show in the documentation is:

// Percent encode . or $ characters to use them in map keys

let mapKey = "New York.Brooklyn"

let encodedMapKey = "New York%2EBrooklyn"

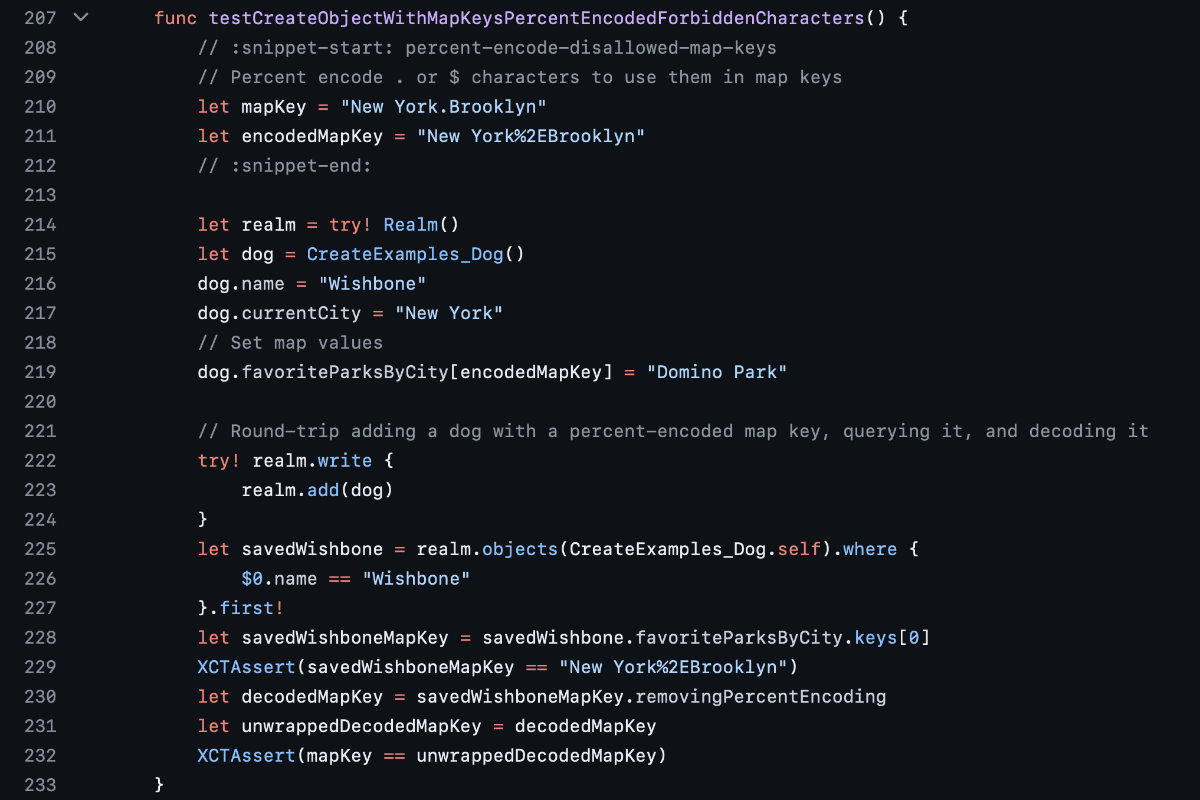

The test for this code example:

func testCreateObjectWithMapKeysPercentEncodedForbiddenCharacters() {

// :snippet-start: percent-encode-disallowed-map-keys

// Percent encode . or $ characters to use them in map keys

let mapKey = "New York.Brooklyn"

let encodedMapKey = "New York%2EBrooklyn"

// :snippet-end:

let realm = try! Realm()

let dog = CreateExamples_Dog()

dog.name = "Wishbone"

dog.currentCity = "New York"

// Set map values

dog.favoriteParksByCity[encodedMapKey] = "Domino Park"

// Round-trip adding a dog with a percent-encoded map key, querying it, and decoding it

try! realm.write {

realm.add(dog)

}

let savedWishbone = realm.objects(CreateExamples_Dog.self).where {

$0.name == "Wishbone"

}.first!

let savedWishboneMapKey = savedWishbone.favoriteParksByCity.keys[0]

XCTAssert(savedWishboneMapKey == "New York%2EBrooklyn")

let decodedMapKey = savedWishboneMapKey.removingPercentEncoding

let unwrappedDecodedMapKey = decodedMapKey

XCTAssert(mapKey == unwrappedDecodedMapKey)

}

In other words, we test the assertion that we make in the documentation.

Testing this gives us a way to verify it’s correct. The behavior we describe matches the execution of the code. We verify that we have correctly understood the problem space.

Seeing it in code helps us confirm that our example makes sense. And the compiler is checking our code for typos and other issues. The code in the docs is code that we actually run, so we can be confident it’s free from errors.

In this case, the code that we show in the documentation is only 3 lines. But its test is 16 lines. There is definitely overhead involved in testing. This is why it’s so important to test what you need to and omit what you can.

When engineers write SDKs and APIs, their tests typically don’t use the APIs like a user. Their tests verify a variety of inputs have the expected outputs for a given code path. But for convenience and performance reasons, they often use abstractions.

Engineers writing tests use dummy data with simple abbreviations because the data doesn’t really matter. They use test framework features and abstractions to capture outputs and confirm the contents. This often results in code that doesn’t look like the code that a developer using the product would write. Their tests may contain:

And it may be difficult for a developer trying to use the product to decipher the intended product usage.

Our Swift SDK recently added support for geospatial data. We provide a variety of shapes to make it easy to query for geospatial coordinates within an area. The SDK’s engineers wrote a very reasonable test for one of these shapes - the GeoPolygon. But it contains a lot of assertions and it’s difficult to decipher the intended usage here:

func testGeoPolygon() throws {

// GeoPolygon require outerRing with at least three vertices and 4 points

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, isNull: true)

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, isNull: true)

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, isNull: true)

// GeoPolygon require outerRing first and last point to be equal to close the Polygon

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!)

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 3, longitude: 3)!, isNull: true)

// GeoPolygon require holes to have at least three vertices and 4 points, and first and last point to be equal for each hole

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, holes: [GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!])

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, holes: [GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!], isNull: true)

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, holes: [GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!], isNull: true)

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, holes: [GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!], isNull: true)

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, holes: [GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 3, longitude: 3)!], isNull: true)

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, holes: [GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!], [GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!], isNull: true)

assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, holes: [GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!], [GeoPoint(latitude: 0, longitude: 0)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 1, longitude: 1)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 2, longitude: 2)!, GeoPoint(latitude: 3, longitude: 3)!], isNull: true)

func assertGeoPolygon(outerRing: GeoPoint..., holes: [GeoPoint]..., isNull: Bool = false) {

if isNull {

XCTAssertNil(GeoPolygon(outerRing: outerRing.map { $0 }, holes: holes.map { $0 }))

} else {

XCTAssertNotNil(GeoPolygon(outerRing: outerRing.map { $0 }, holes: holes.map { $0 }))

}

}

// Using Simplified initialisers

XCTAssertNotNil(GeoPolygon(outerRing: [(40.0096192, -75.5175781), (60, 20), (20, 20), (-75.5175781, -75.5175781), (40.0096192, -75.5175781)]))

XCTAssertNil(GeoPolygon(outerRing: [(40.0096192, -75.5175781)]))

XCTAssertNotNil(GeoPolygon(outerRing: [(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (0, 0)], holes: [[(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (0, 0)]]))

XCTAssertNotNil(GeoPolygon(outerRing: [(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (0, 0)], holes: [(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (0, 0)], [(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (0, 0)]))

XCTAssertNil(GeoPolygon(outerRing: [(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (0, 0)], holes: [[(0, 0)]]))

XCTAssertNil(GeoPolygon(outerRing: [(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (0, 0)], holes: [[(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3)]]))

XCTAssertNil(GeoPolygon(outerRing: [(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (0, 0)], holes: [(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (0, 0)], [(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3)]))

}

The documenation test for a query using this geospatial shape looks like this:

func testQueryGeospatialData() {

let realm = try! Realm(configuration: config)

// :snippet-start: geopolygon

// Create a basic polygon

let basicPolygon = GeoPolygon(outerRing: [

(48.0, -122.8),

(48.2, -121.8),

(47.6, -121.6),

(47.0, -122.0),

(47.2, -122.6),

(48.0, -122.8)

])

// Create a polygon with one hole

let outerRing: [GeoPoint] = [

GeoPoint(latitude: 48.0, longitude: -122.8)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 48.2, longitude: -121.8)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.6, longitude: -121.6)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.0, longitude: -122.0)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.2, longitude: -122.6)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 48.0, longitude: -122.8)!

]

let hole: [GeoPoint] = [

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.8, longitude: -122.6)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.7, longitude: -122.2)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.4, longitude: -122.6)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.6, longitude: -122.5)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.8, longitude: -122.6)!

]

let polygonWithOneHole = GeoPolygon(outerRing: outerRing, holes: [hole])

// Add a second hole to the polygon

let hole2: [GeoPoint] = [

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.55, longitude: -122.05)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.55, longitude: -121.9)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.3, longitude: -122.1)!,

GeoPoint(latitude: 47.55, longitude: -122.05)!

]

let polygonWithTwoHoles = GeoPolygon(outerRing: outerRing, holes: [hole, hole2])

// :snippet-end:

// :snippet-start: geopolygon-query

let companiesInBasicPolygon = realm.objects(Geospatial_Company.self).where {

$0.location.geoWithin(basicPolygon!)

}

print("Number of companies in basic polygon: \(companiesInBasicPolygon.count)")

let companiesInPolygonWithTwoHoles = realm.objects(Geospatial_Company.self).where {

$0.location.geoWithin(polygonWithTwoHoles!)

}

print("Number of companies in polygon with two holes: \(companiesInPolygonWithTwoHoles.count)")

// :snippet-end:

XCTAssertEqual(2, companiesInBasicPolygon.count)

XCTAssertEqual(1, companiesInPolygonWithTwoHoles.count)

}

While it’s still a lot of code, the documentation test actually uses the API like a user would. It creates objects with variable names that clearly describe the objects, versus the inline object creation that the engineering test uses. It shows a few different object examples of progressive complexity to demonstrate the object type’s usage. And it actually uses the object to query geospatial data from the database.

This code example and test much more clearly demonstrates the API’s usage. The engineering tests verify the provided inputs have the expected outputs for a variety of conditions.

This point might be controversial, but for pragmatic and maintenance reasons, your documentation code examples and tests should demonstrate common usage patterns and best practices. Documentation code examples and tests don’t have to cover every case.

I say this is potentially controversial because developers always want more code examples - and more comprehensive code examples - in documentation. I count myself in that bucket. When I’m using Apple’s developer documentation to work on my iOS/macOS apps, or GitHub’s API documentation to work on PR Focus, I often run into cases where the basic examples in the documentation don’t cover my specific use case or answer a question I have.

But as a matter of resources, I have never encountered or heard of an organization that has enough technical writers on staff to write thorough, comprehensive code examples for every situation. There just isn’t enough time. The best we can hope for is to cover the common usage patterns.

We have a documentation page that describes how to set a log level, and how to define a custom logger. The code example for setting a custom logger looks like this:

// Create an instance of `Logger` and define the log function to invoke.

let logger = Logger(level: .detail) { level, message in

// You may pass log information to a logging service, or

// you could simply print the logs for debugging. Define

// the log function that makes sense for your application.

print("REALM DEBUG: \(Date.now) \(level) \(message) \n")

}

We’re not showing a specific implementation here, because there are so many different analytics and logging options. So we just show a common usage pattern - declare an instance of Logger() and define the log function to invoke - and let you populate it with what your app needs.

The test for this code example is similarly vague. We’re just creating a string variable in our test, and appending log entries to the string variable. We assert that the variable is not empty in the test, but we’re not checking for anything specific, because the specifics don’t matter. We’re only trying to confirm that this functionality works the way we say it does.

func testDefineCustomLogger() {

let app = App(id: YOUR_APP_SERVICES_APP_ID)

var logs: String = ""

// :snippet-start: define-custom-logger

// Create an instance of `Logger` and define the log function to invoke.

let logger = Logger(level: .detail) { level, message in

logs += "\(Date.now) \(level) \(message) \n" // :remove:

// You may pass log information to a logging service, or

// you could simply print the logs for debugging. Define

// the log function that makes sense for your application.

print("REALM DEBUG: \(Date.now) \(level) \(message) \n")

}

// :snippet-end:

Logger.shared = logger

XCTAssert(logs.isEmpty)

let expectation = XCTestExpectation(description: "Populate some log entries")

app.login(credentials: Credentials.anonymous) { (result) in

switch result {

case .failure(let error):

fatalError("Login failed: \(error.localizedDescription)")

case .success(let user):

print("Login as \(user) successful")

XCTAssert(!logs.isEmpty)

expectation.fulfill()

}

}

wait(for: [expectation], timeout: 5)

}

Developer documentation is always a balance of guessing what it is safe to assume, and figuring out what you need to explicitly call out. In some cases, we rely on developers to have enough knowledge of their language’s features to omit specific details. In other cases, we may explain and demonstrate a concept “earlier” in the user journey, but assume you already know it and omit that boilerplate code in “later” code examples.

We do this both in the examples we show in the documentation, and in our tests.

This is more uncertain in a world where developers come into documentation through searching for something specific. We can’t be certain that a developer has seen the “earlier” example where we provide more of the boilerplate. So the balancing act is more precarious, and liberal cross-linking of documentation is a useful tool.

In one example in our documentation, we show using the language’s built-in error handling mechanism to handle an error when opening the database:

do {

let realm = try Realm()

// Use realm

} catch let error as NSError {

// Handle error

}

But doing that in every example adds a lot of extra complexity. Code would become more difficult to follow if we nested every piece of failable code in a do/catch block. And that adds a lot of extra lines to examples - and cognitive overhead for developers to spot the relevant lines of code - if we do this in every example.

So in most of our code examples after this one, we omit the do/catch block when opening the database and just use the failable version. We rely on developers to know they need to do this safely, and not use an exact copy/paste of our code in their apps:

// Instantiate the class and set its values.

let dog = Dog()

dog.name = "Rex"

dog.age = 10

// Get the default realm. You only need to do this once per thread.

let realm = try! Realm()

// Open a thread-safe transaction.

try! realm.write {

// Add the instance to the realm.

realm.add(dog)

}

In this case, both operations with a try! can fail - opening the database and attempting to write the object to the database. But we don’t make any effort to safely catch and handle those failures. We want to quickly demonstrate the usage to developers, and we are using the language features - the try! to telegraph the failure points in this example instead of showing actually safely handling them.

Similarly, in our tests, we may test some functionality in some code examples but omit those tests in other code examples. For example, we pull the code above directly from our test suite, so we can be sure it’s free of typos and compiles. But it does not have any test coverage. That’s because we have other examples where we test adding objects to the database and retrieving them. If we built on this example to do something more complex that does not have any test coverage, we’d add tests for those more complex operations.

This point trips people up sometimes, but we’ve decided it is a best practice to not show “wrong” code in code examples. For example, you might want to say something like “this query throws an error because…” and show an example of code that will throw an error.

Inevitably someone copies and pastes the code and then files an issue because it didn’t work. It doesn’t matter how much text you put around the code - you can leave a comment right above the offending line - but someone won’t read the note that this is “wrong” and will try to use it. This used to happen to us, so we stopped doing it.

The only possible exception is if there is an API that people commonly misuse. We might add a commented-out line and clear annotation showing incorrect usage above a line showing correct usage.

This example does not exist in our documentation, because we’ve removed “wrong” examples. But it illustrates the issue - showing code that throws an error, but looks valid:

let realm = try! Realm()

try! realm.write {

// You can't add an embedded object by itself to the database

// Embedded objects can only exist within the context of a parent object

realm.add(embeddedAddressObject)

}

If it’s really important to show the “wrong” code, only do it as commented-out code with plenty of explanation, and follow it with the correct usage:

let realm = try! Realm()

try! realm.write {

// You can't add an embedded object by itself to the database

// Embedded objects can only exist within the context of a parent object

// This would cause an error:

// realm.add(embeddedAddressObject)

// Instead, assign it to the parent object and add the parent

person.address = embeddedAddressObject

realm.add(person)

}

The purpose of documentation code examples and tests isn’t to recreate comprehensive engineering tests that cover all the possible inputs and outputs and catch edge cases. We can and should leave that to the engineering team. The point of testing the code that shows how to use our product is to ensure that it compiles, runs, and works the way we say it does.

That makes it possible for us to limit the scope of our tests. We aren’t trying to be thorough. We are trying to be accurate.

The tests above in the “Use the APIs you document” section demonstrate the difference between comprehensive engineering tests and our documentation tests.

The engineers who write the SDKs and APIs we document can be your allies when it comes to testing your docs code examples. Learning test frameworks and how to write tests can be daunting for documentarians. We can lean on the tools that the engineering teams use when we write our tests. Read the engineering tests. See how they use assertions and how they handle different cases. If you have questions about why they have selected a specific test framework, or why they’ve done a specific thing in the tests, ask.

The process of talking about testing can lead to valuable documentation around how to test code that uses your SDK or API. Building a relationship with the engineers who write the code, and talking about how to test it, can strengthen the bonds between teams, and appreciation for the different skills and perspectives that each party brings.