Audit - Modeling Code Example Metadata

In which we decide what information to store, and how.

A few months ago, I wrote about why you should test docs code examples. Today, I’m going to look at how to test docs code examples.

The specifics may vary from team to team and tool to tool, but this is the broad shape of what this process looks like:

In another post, I’ll dive deeper on what your docs code examples and tests should cover. For this topic, I’ll follow a code example from the unit test suite to publishing the docs.

The first step is to write your docs examples in unit test suites. Use a test suite that is idiomatic for the language/framework in which you’re writing code examples.

This may mean you’ll have multiple unit test suites if your docs cover multiple languages or frameworks.

For example, on my team, we write docs for 9 SDKs. This means we have 9 different unit test suites that work in ways that are idiomatic for their languages/frameworks. For example:

test package maintained on pub.dev.This means that as writers, we have to have a lot of tools installed. And we have to learn a lot of different testing systems and paradigms.

In the past, we have mainly had one writer working on one or maybe two SDKs. So that writer only had to know one or two test systems.

These days, we’re a much smaller team and our surface area has grown. We all have to be set up with more than one SDK’s test tools. And we must be familiar enough with the different systems to write examples/tests for more than one SDK.

Learning these tools does take time. But a lot of the knowledge is transferrable with some minor differences in syntax and tooling.

I can’t overstate how helpful it is to use tooling that is idiomatic for the language. This enables you to write documentation about how to actually test the product. For example, one of my colleagues wrote this excellent guidance about how to write tests that use our product: Java SDK/Testing. That came from US, the docs team, using idiomatic testing tools to create integration and unit tests for our code examples.

Using the tools that developers use also helps to build empathy with developers. And it helps us spot rough edges that we can raise to engineering for product improvements.

Let’s take a look at a real example in our documentation. Our C++ SDK recently added the ability to close a database. It also included related methods to check that the database is closed and any objects from the database are invalidated after it’s closed.

The unit test for this documentation example looks like this:

TEST_CASE("Close a realm example", "[write]") {

auto relative_realm_path_directory = "open-close-realm/";

std::filesystem::create_directories(relative_realm_path_directory);

std::filesystem::path path =

std::filesystem::current_path().append(relative_realm_path_directory);

path = path.append("some");

path = path.replace_extension("realm");

// :snippet-start: close-realm-and-related-methods

// Create a database configuration.

auto config = realm::db_config();

config.set_path(path); // :remove:

auto realm = realm::db(config);

// Use the database...

// :remove-start:

auto dog = realm::Dog{.name = "Maui", .age = 3};

realm.write([&] { realm.add(std::move(dog)); });

auto managedDogs = realm.objects<realm::Dog>();

auto specificDog = managedDogs[0];

REQUIRE(specificDog.name == "Maui");

REQUIRE(specificDog.age == static_cast<long long>(3));

REQUIRE(managedDogs.size() == 1);

// :remove-end:

// ... later, close it.

// :snippet-start: close-realm

realm.close();

// :snippet-end:

// You can confirm that the database is closed if needed.

CHECK(realm.is_closed());

// Objects from the database become invalidated when you close the database.

CHECK(specificDog.is_invalidated());

// :snippet-end:

auto newDBInstance = realm::db(config);

auto sameDogsNewInstance = newDBInstance.objects<realm::Dog>();

auto anotherSpecificDog = sameDogsNewInstance[0];

REQUIRE(anotherSpecificDog.name == "Maui");

REQUIRE(sameDogsNewInstance.size() == 1);

newDBInstance.write([&] { newDBInstance.remove(anotherSpecificDog); });

auto managedDogsAfterDelete = newDBInstance.objects<realm::Dog>();

REQUIRE(managedDogsAfterDelete.size() == 0);

}

If you’re curious, the full test file with model definition and #includes is available here: docs-realm/examples/cpp/local/close-realm.cpp

Ok, so we’ve got some code that shows the example we want to show. But it’s also got a lot of other test setup and assertions and stuff that we don’t necessarily want to show in the docs. So - how do we get the example out of the test suite and into the docs?

You could manually copy the relevant bits and paste them into the docs directly. Unfortunately, that’s prone to two classes of errors:

My team wrote a tool (before I came along, I can’t take any credit for this!) that lets you excerpt bits from the unit test into a generated output file. It’s called Bluehawk, and it’s open source - you can check it out here: Bluehawk.

Bluehawk has two parts:

Bluehawk is a really powerful tool that lets us focus on the code we need to show to communicate to developers how to use the product, and omit the rest. It lets us easily make concise, tested code examples from our test suites.

After creating or updating test files, we run Bluehawk to generate output files containing just the parts of the test files that we want to show in our documentation. We store these output files in a generated directory in our docs source. Any file we pull from there to include in our docs is a generated code example from a unit test suite.

When we make changes to a code example file, our process includes generating updated examples for the test suite. This gives us confidence that we didn’t forget to update an example after updating our tests.

In the example test above, check out this part:

// :snippet-start: close-realm

realm.close();

// :snippet-end:

The snippet-start and snippet-end comments are Bluehawk markup tags. They tell the CLI where to start and end the excerpt. The identifier you pass with the snippet-start tag becomes part of the name of the example.

After marking up the file, I would run Bluehawk to generate output files from this test suite. So, I run this command:

bluehawk snip $CPP_EXAMPLES/local --ignore build -o $GENERATED_EXAMPLES

And this creates an output file named close-realm.snippet.close-realm.cpp in the generated examples directory. That snippet contains this code:

realm.close();

Bluehawk gets really cool when you do some of the more advanced things it can do. In the example above, you can see another snippet-start and snippet-end tag - but this one has a remove-start and remove-end section.

// :snippet-start: close-realm-and-related-methods

// Create a database configuration.

auto config = realm::db_config();

config.set_path(path); // :remove:

auto realm = realm::db(config);

// Use the database...

// :remove-start:

auto dog = realm::Dog{.name = "Maui", .age = 3};

realm.write([&] { realm.add(std::move(dog)); });

auto managedDogs = realm.objects<realm::Dog>();

auto specificDog = managedDogs[0];

REQUIRE(specificDog.name == "Maui");

REQUIRE(specificDog.age == static_cast<long long>(3));

REQUIRE(managedDogs.size() == 1);

// :remove-end:

// ... later, close it.

// :snippet-start: close-realm

realm.close();

// :snippet-end:

// You can confirm that the database is closed if needed.

CHECK(realm.is_closed());

// Objects from the database become invalidated when you close the database.

CHECK(specificDog.is_invalidated());

// :snippet-end:

When I run the Bluehawk CLI to excerpt this file, the output is a file named close-realm.snippet.close-realm-and-related-methods.cpp. That snippet contains this code:

// Create a database configuration.

auto config = realm::db_config();

auto realm = realm::db(config);

// Use the database...

// ... later, close it.

realm.close();

// You can confirm that the database is closed if needed.

CHECK(realm.is_closed());

// Objects from the database become invalidated when you close the database.

CHECK(specificDog.is_invalidated());

You can see Bluehawk omits the section between the remove tags from the output snippet. This makes it easy to remove various test elements that you don’t want or need to show in the output example. Bluehawk can also do cool stuff like replace text from our example files. We use this to rename complicated variable names to something simpler. It has even more advanced capabilities. Check out the repo for docs and a couple of example videos made by yours truly.

Now that we’ve got generated code examples from our test suites, we need to include those examples in our documentation.

Our team uses Sphinx - with a few custom bits and bobs - to create our documentation. Sphinx uses reStructuredText, which gives us several ways of showing code blocks. Our team uses the literalinclude directive to include the contents of an external file in our page.

We can use the literalinclude directive to refer to our generated file that contains our Bluehawk output from our test suite and include it in our docs.

So now we have our tested example in our documentation! We know the example works because we’re testing it ourselves. We know there are no typos or errors in the code example because we’re not manually excerpting it. Our tool is faithfully copying the content. We have eliminated entire classes of negative docs feedback by testing the code examples and using a tool to excerpt them and include them in our docs. We’ve removed a whole lot of possible human error.

Buuuuut - we can go one step farther and run our tests in CI every time we make changes.

Using literalinclude, it’s very simple to include our example above:

.. literalinclude:: /examples/generated/cpp/close-realm.snippet.close-realm-and-related-methods.cpp

:language: cpp

We have additional options, such as the ability to emphasize lines or include line numbers in the documentation page. But this example is pretty simple and does not need those additional options.

Tests are great - when you run them! But how can we be sure a busy docs person didn’t make changes to a file and forget to run the tests? Or - how can we be sure that changes to one part of the SDK didn’t also break other tests?

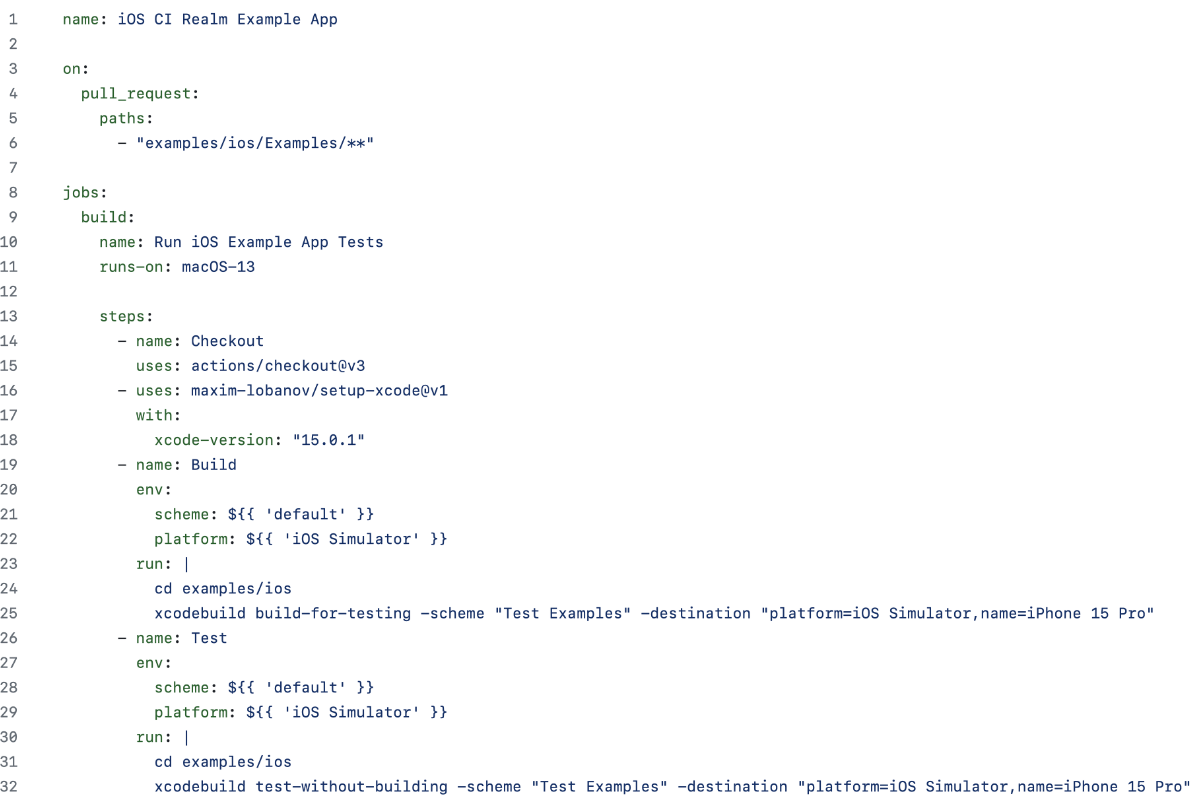

Our team uses GitHub workflows to run our documentation test suites when we change them. These test suites show up as named checks on the pull request. They get a green check if all the tests pass, or it a red X if the CI fails for some reason.

When a test fails in CI and it’s related to the change we’re making, we don’t merge the pull request until the test passes. If a test fails in CI and it’s not related to the change we’re making, we may still fix it before merging. Or we may make a Jira ticket to fix it later if the PR is time-sensitive. In either case, we do the work to make the test pass.

Sometimes, this exposes bugs or regressions in the product. We can share those with engineering. In other cases, an issue may arise because a dependency changes. We can fix those by updating dependencies. We may want to add documentation to help other devs troubleshoot these issues.

In any case, running the tests in CI give us another layer of confidence that our docs code examples work - because they’re tested!

This is the workflow that runs on the test file I’m using in this article. Whenever someone makes a PR to our docs repository that includes changes in the examples/cpp/local/ directory, this CI workflow builds and runs the test suite. It shows as a check on the pull request named “C++ Local Example Tests”.

name: C++ Local Example Tests

on:

pull_request:

paths:

- "examples/cpp/local/**"

jobs:

tests:

runs-on: macOS-12

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: Build

run: |

cd examples/cpp/local

mkdir build && cd build

cmake ..

cmake --build .

- name: Test

run: |

cd examples/cpp/local/build

./examples-local

As a bonus, if we’re working on a test suite where we’re not as familiar, we can look at the workflow to figure out how to run it. This serves as a form of meta documentation to tell me how to run this test suite.